If you’ve gone down rabbit holes in search of elusive ancestors and found yourself in a maze-like world of tunnels and loops and switchbacks, you’ll understand the tale I’m about to share. Those of you who’ve read The Cowkeeper’s Wish will know who Jennie (Jane) is: one of the cowkeeper’s granddaughters, married in 1890 to a shoemaker named Richard Vanson, and our great-great aunt. Some of the Vanson story we’ve told in the book, and some in a previous post. They’re an interesting bunch. From a brush with the law to their connection with one of Jack the Ripper’s victims, this part of our family tree has skeletons aplenty in its closet, and I stumbled across a few more while trying to puzzle out what had become of Jennie and her daughters after Jennie’s husband Richard died of tuberculosis in 1911.

If you’ve gone down rabbit holes in search of elusive ancestors and found yourself in a maze-like world of tunnels and loops and switchbacks, you’ll understand the tale I’m about to share. Those of you who’ve read The Cowkeeper’s Wish will know who Jennie (Jane) is: one of the cowkeeper’s granddaughters, married in 1890 to a shoemaker named Richard Vanson, and our great-great aunt. Some of the Vanson story we’ve told in the book, and some in a previous post. They’re an interesting bunch. From a brush with the law to their connection with one of Jack the Ripper’s victims, this part of our family tree has skeletons aplenty in its closet, and I stumbled across a few more while trying to puzzle out what had become of Jennie and her daughters after Jennie’s husband Richard died of tuberculosis in 1911.

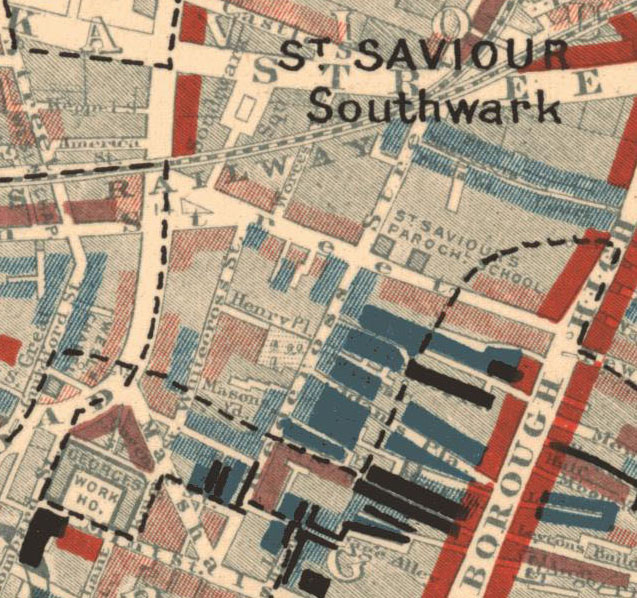

For people of our family’s social standing, it wasn’t easy to be a widow in the early days of the 20th century, before pensions and social safety nets, and it was even harder if you had children to worry about. Two months after her husband’s death, forty-year-old Jennie wrote on the census form in a messy scrawl that she lived at 30 Burdett Chambers in Lambeth (the same address she’d shared with her shoemaker husband), along with two of her daughters: eighteen-year-old Florence, a tailoress, and the youngest, Ada, who was four. Jennie reported working as an office cleaner, and although she also wrote answers to the questions regarding her years of marriage and children, someone, presumably the enumerator, stroked through the numbers with a heavy pen, since as a widow she need not have recorded them. But the information she’d penned remained legible, and what I read offered no surprises: she’d been married for twenty years, and had borne six children, of whom four were living and two were dead. A further census search revealed that her other surviving daughters, Nellie Jane and Alice, resided nearby. The eldest, nineteen-year-old Nellie Jane, lived at 45 Trinity Square in the neighbouring Borough, in the home of John Alexander, a surgeon and clinical assistant at the Evelina Hospital for Children. Dr. Alexander had taken over the practice operated at the Trinity Square address by his father, Charles Linton Alexander, who had died in 1887. Nellie Jane was John Alexander’s “general servant, domestic”, so her day was spent sweeping, dusting, scrubbing, laying fires and serving at mealtimes.

I found Jennie’s other daughter Alice, also nearby, living with her uncle George Vanson, his wife Edith and their daughter Isabel a few blocks east along Waterloo Road from Burdett Street. Despite her young age, fourteen-year-old Alice had a more unusual job than her sisters or her mother, employed as an apprentice perruquier (wig-maker) for H&M Rayne, a company that made costumes for the theatre industry.

Cousin Isabel, a couple of years older, also worked for Rayne, learning the skill of costume-making. H&M Rayne was headquartered just steps from Uncle George’s Webber Row address in Lambeth, so given the close proximity of the costumier, living with her Uncle George was a sensible choice for Alice.

If Alice and Isabel’s jobs sound interesting, Uncle George and Aunt Edith’s were more mundane. George was a dock worker, one of thousands of casual, unskilled labourers whose livelihood depended on what work was available when he showed up at the docks each morning hoping to be selected for a crew. A docker’s work was hard, dirty, and poorly paid, and a shift might last an hour or two, or stretch into the night, and depending on the cargo – lead, asbestos, fertilizers – could be dangerous. Edith toiled as a charwoman, an occupation not unlike George’s in that it was hard work and the pay meagre. To be a char was to be at the bottom of the domestic service hierarchy, and for most women, charing was a last resort before knocking on the workhouse door. George and Edith were barely getting by, so Alice and Isabel’s income was surely welcome.

Edith was about thirteen years older than George, and he was her second husband. Her first, Frank Pitcher, had been an inmate at Cane Hill Asylum, a place that readers of The Cowkeeper’s Wish will be familiar with. Admitted in 1888 when Frank and Edith had been married eighteen years, his admittance documents say he’d been “getting gradually worse for four years” and that he’d been “living apart” from Edith for some time. Poor Law records describe him as a “lunatic” who refused medicine, and occasionally food, believing them to be poisoned. He wandered aimlessly, his case notes state, required constant supervision and was “very wet and dirty night and day.” The casebook also revealed that his next-of-kin was his stepmother, as his wife’s whereabouts were unknown.

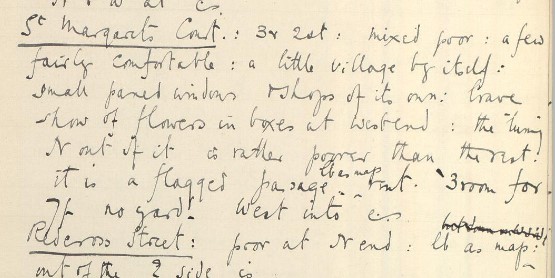

But in fact, Edith hadn’t gone far. I found her in 1891, living with her children in St Margaret’s Court, a street described by social investigators as “a bad quarter,” and yet also “a little village by itself” with a “brave show of flowers at west end.” St. Margaret’s Court was one of many narrow passages that led off Red Cross Street in Southwark where Jennie Vanson resided, newly wed to Richard, and was presumably where Edith was still living when she met Richard’s brother, George. Frank Pitcher remained a lunatic asylum inmate until his death in 1893, and three years after he died, in 1896, Edith married George Vanson. In my search for the trail of Jennie and her daughters, the coincidence of Cane Hill was interesting, but other than that, I dismissed George and Edith as just another of many poor couples that connected tangentially to The Cowkeeper’s Wish. But in fact the lives of George and Edith and Jennie and her daughters would be inextricably linked, and as I traced the path of the Vanson women, George would insistently appear, and eventually take on a new importance.

After finding Jennie and her girls on the 1911 census, and relegating the story of George and Edith to a sidebar, things got complicated. I looked for anything that would move the Vanson women forward in time, and discovered that Alice, our young perruquier, married in 1918 to an older man named Arthur Polley and moved to northeast London, where Arthur had his own business as a retail grocer. Ada, just four years old in 1911, married Edward McCarthy in 1932, and Florence, the tailoress, wed Fred Thomas, a carman, in 1914, and had at least two children, both born during the war years.

All of Jennie’s daughters, then, except the oldest, Nellie Jane, who’d worked for the doctor in Trinity Square, were so far accounted for. Nellie Jane proved somewhat trickier. In my hunt for her I came across a 1936 marriage index entry for a 45-year-old Nellie Jane Vanson and a 36-year-old Reginald Thomas Sanson in Eastbourne, Sussex. At first it seemed silly given the rhyme of the last names and Nellie’s age, and what on earth would a Vanson girl, come from generations of working class Londoners, be doing in a resort town on England’s south coast? Surely it wasn’t Jennie’s daughter. But then I found a death index entry in Eastbourne for a Jane Vanson, age 84 in 1955 (so born in 1871 as was our Jennie), and I reconsidered the Vanson-Sansons.

Eastbourne in the 1930s wasn’t a very big place, and I reasoned that if Jennie had died there in 1955 there might have been an obituary placed in the local paper, and it might tell me if I had the right woman. I wrote to the cemetery board in Eastbourne to ask about Jane Vanson’s burial record, and I wrote to the Eastbourne Library (which holds the Eastbourne Herald newspaper archives) to see if they could find an obituary. Both replied, and from the cemetery board I learned the exact date of death and an address on Cavendish Avenue, Eastbourne, and from the library I received an obituary for Nellie Jane that gave the same address. Things were falling into place, and it certainly seemed that this was our Jennie and her oldest daughter Nellie Jane. But how had they come to be in Eastbourne, and when, and had they come together? Was it just Nellie Jane and Jennie or was other family in Eastbourne too?

I went back to the Electoral Rolls for London and continued to fill in the missing years, first coming across Flo and Fred in 1919 (with Fred’s rank, regiment and serial number, so he’d been in the Great War) at #2 Brigade House, Southwark Bridge Road. Brigade House was part of the London Fire Brigade’s Southwark headquarters, so perhaps Fred’s job as a carman meant he drove one of the horse and wagon fire engines. In 1929, Flo’s Uncle George, the dockworker, husband of Edith, suddenly popped up at their Brigade House address. But by 1933, Fred was alone at #2. No Flo, no George. Within two years, Fred had a new partner at #2, so maybe Flo died, although I’ve found no death record that matched. George, too, was gone, but he turned up at Rowton House, a hostel for down and out men on Churchyard Row, behind St Gabriel Street in Newington.

That George’s circumstances were so reduced was a sad turn of events, and yet things might have been much worse. The Rowton House lodging houses were the best of what was available in terms of shelter for vagrants and poor single men according to the author George Orwell, who’d written from personal experience of homelessness in London in 1933. The facility where George lived had been built in 1897, the third such structure of its kind erected by Montagu Corry, 1st Baron Rowton. Lord Rowton had sought to improve the lot of poor single working men whose choices, if they had no home of their own, had ranged from filthy, bug-infested dosshouses and spartan hostels to penny sit-ups, where a penny bought a man a spot on a bench in a warm building, but did not allow him to lie down, to a park bench with the likelihood of a constable prodding him to move along.

When Rowton House in Newington Butts opened on Christmas Eve in 1897, there were 805 private sleeping cubicles with sheets, blankets, a quilt and a chamber pot, and pegs on which a fellow could hang his trousers. There were bathing facilities and lavatories in the basement, and a dining room on the ground floor that seated 400. A hot meal could be had for pennies, or a man could cook his own. There was a reading and smoking room, a barber and a tailor and a shoemaker. A man could pay for his room a week at a time in advance, and guarantee his spot, or he could take his chances and hope for a room, paying nightly. The newspapers of the day were impressed with Rowton House, and soon after the Newington location opened its doors, the South London Chronicle wrote that “the utmost good fellowship prevailed” among the inmates, and “the bill of fare [on Christmas Day] would not have shamed a high-class restaurant.”

By the time George became a resident in 1932, a wing had been added, increasing Rowton’s capacity by several hundred beds. On a night with a full house, George’s snores would have joined in a chorus with more than 1,000 other souls tucked into tiny cubicles over six floors. An account written in 1935 for The Sunderland Echo gives an idea of what life was like in Rowton House for George and men like him, past seventy and likely living on the pittance of a government Old Age Pension. He’d have kept the same room at the hostel by paying the weekly amount, and for a few more shillings he had the option of renting a locker where he could store his few possessions. In the morning, a bell-ringer travelled the hallways rousing George and the rest of the residents from their cubicles, and after a wash at the basins in the basement he and some of the other Rowton men gathered in the dining hall, making tea if they had a bit of leaf and a pot and a cup stowed in their locker, or purchasing porridge, a boiled egg and toast for a penny from the canteen. After breakfast, George might have spent some of the day in the smoking room – being illiterate he’d have had no use for the books in the reading room, and all Rowton Houses had strict rules against card playing. If the weather was fair, perhaps he’d have taken a stroll and sat for an hour on a bench in the sun before returning to Rowton in time for the evening meal. Afterwards, those with a few extra coins in their pocket would sally forth to the pubs for a pint. Those without money to spare had an early night in their cubicles. The Sunderland Echo reporter, when he’d arrived at the hostel to research his article, had received a warning from one of the officials at the house: “Keep to yourself, chum; there’s some queer men in here.” And yet the writer found the Rowton House inmates to be mostly “respectable working men, quietly dressed,” even if one or two “showed their toes sticking through the ends of their boots.”

George lived at Rowton House for thirteen years, a spartan existence toward the end of a life that had held few comforts. I wanted to know more about how he got there. In 1911 he’d been working the docks and sharing his roof with wife Edith, daughter Isabel, and niece Alice, the apprentice perruquier. In 1929 he was presumably a boarder with another niece, Alice’s sister Flo and her husband Fred. Where had George been in the years in between?

A further search located George on the Land Tax register for 1916, renting a house in St Gabriel Street, Newington Butts, a short stroll from Rowton House. The 1918 Electoral Rolls confirmed the address, and also offered the surprise of his sister-in-law, our Jennie, the mother of Flo and Alice, living with him. I was intrigued. Had George’s wife Edith died? If so, I could find no recent record. I checked for a marriage record for George and his brother’s widow, but found nothing there either. George would have been 55 and Jennie 42 in 1918, and I supposed their co-habitation could have simply been a platonic arrangement of convenience, two middle-aged relatives with next to no money supporting one another in shared lodgings. The Electoral Rolls confirmed that this relationship, whatever it was, continued until 1929, when 66-year-old George turned up at Flo and Fred’s. Did Jennie kick him out? Or did George leave on his own? And after all that time, why?

Those kinds of questions are likely never to be answered one hundred years on, and yet, it’s difficult to stop looking. I turned my focus back to Eastbourne and discovered that another of Jennie’s children, Alice, the one-time perruquier who’d married the greengrocer Arthur Polley, had also moved to Eastbourne. In 1939, the couple had still been running their grocery in northeast London, but the 1948 Kelly’s Street Directory for Eastbourne yielded an address for Arthur and Alice just a few doors down from Nellie Jane and Reginald Sanson’s Cavendish Avenue address in Eastbourne. When he died in 1951, Arthur was relatively young at just 63. Perhaps he’d been unwell, and he and Alice had moved to the seaside for his health. That left Jennie and Ada in London.

Ada, Jennie’s youngest, had been not quite five years old when her father Richard died of tuberculosis. Most likely she barely remembered him. The man to feature more prominently in her life as a father figure had been her uncle George, with whom she and her mother lived for so many years. But in 1929, George moved to Flo’s, and Ada too left when she married Edward McCarthy, a loader for the London and North Eastern Railway working out of the Farringdon Street Goods Station.

Mother and daughter remained in close proximity, though, living in different blocks of the Guinness Buildings on Brandon Street in Walworth, tenement housing erected for the urban poor that consisted of spare, two room flats with no running water or electricity, a shared toilet and sink on the landing, and pay access to bathing facilities two days of the week. They resided separately at Guinness Buildings until Jennie moved in 1954 to Eastbourne, where Nellie Jane, her husband Reginald, and the widowed Alice lived.

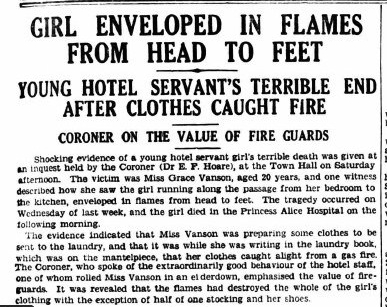

This might have been the end of the story, minus the unknowable details, but for a random search I did on the British Newspaper Archive website, completely apart from my Vanson research. I forget the exact parameters I searched on, but a March, 1934 headline I came across was provocative and sensationalist: “Girl Enveloped in Flames from Head to Feet. Young Hotel Servant’s Terrible End After Clothes Caught Fire.” The article appeared on the front page of the Eastbourne Gazette, and told of a young woman employed by the South Cliff Hotel in Eastbourne as a live-in chambermaid and waitress. Just off duty, the girl had been alone in her bedroom making notes in the laundry logbook when the skirt of her uniform caught fire on the gas flame of room’s heater.  She was immediately engulfed in flames, and ran screaming into the nearby hotel kitchen where a porter had the presence of mind to fetch an eiderdown quilt and smother the flames. Her clothing was burnt completely away, and the porter, with the help of other staff who’d come running, laid her on her bed and covered her with blankets. She was admitted to the Princess Alice Hospital “suffering from extensive burns on her arms, legs, abdomen, chest and all over her back up to her neck,” and died the next day “due to shock following severe burning.” The inquest reported that there’d been no guard on the gas fireplace, but acknowledged that “most of us do use [gas fires] in this way.” The hotel was never considered to be culpable, although the Coroner made a point of saying that guards could be had “at very little extra cost, and they are well worth it, because they are just the thing to prevent clothes from igniting.” It was a sad tale indeed, but most interesting for me was that the young chambermaid’s name was Grace Vanson.

She was immediately engulfed in flames, and ran screaming into the nearby hotel kitchen where a porter had the presence of mind to fetch an eiderdown quilt and smother the flames. Her clothing was burnt completely away, and the porter, with the help of other staff who’d come running, laid her on her bed and covered her with blankets. She was admitted to the Princess Alice Hospital “suffering from extensive burns on her arms, legs, abdomen, chest and all over her back up to her neck,” and died the next day “due to shock following severe burning.” The inquest reported that there’d been no guard on the gas fireplace, but acknowledged that “most of us do use [gas fires] in this way.” The hotel was never considered to be culpable, although the Coroner made a point of saying that guards could be had “at very little extra cost, and they are well worth it, because they are just the thing to prevent clothes from igniting.” It was a sad tale indeed, but most interesting for me was that the young chambermaid’s name was Grace Vanson.

In all my efforts to discover the story of Jennie (Jane) Vanson and her daughters, I’d never come across anyone named Grace, but I was suddenly certain, in the way one can be with a hunch, that this was another of Jennie’s girls. The newspaper articles referring to the tragedy of Grace’s death quoted a sister, Miss Mary Jane Vanson, thanking the South Cliff Hotel’s management and staff “who had done everything that was possible for her sister” and I wondered, might the reporter have gotten it wrong, and Mary Jane was actually Nellie Jane? Elsewhere in the paper was an item of thanks “to all friends for the beautiful floral tributes and letters of sympathy” posted by Mrs. Jane Vanson and family. The Vanson story, I felt sure, had not yet revealed its final chapter.

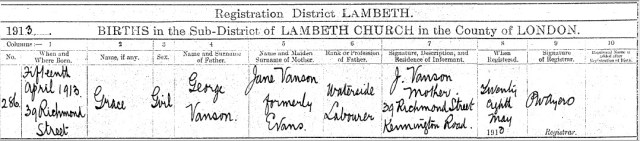

Grace was 20 years old when she died in March of 1934, which meant she’d been born around 1914. I searched for, and found, an entry in the indexes for a birth registration that fit only too well – a Grace Vanson born in Lambeth in 1913 to a mother with the maiden name of Evans. Our Jennie had been born Jane Evans, but her husband Richard had been dead two years by the time of this Grace’s birth. If Grace was indeed Jennie’s daughter, who was the father? The only way to find out was to send for the birth registration, and when it arrived, it confirmed what I had suspected: Grace’s parents were Jane Vanson “formerly Evans” and her brother-in-law, George Vanson, a “waterside labourer”.

So how had the relationship that produced a daughter come about? Had George been a stalwart presence, supporting Jennie during Richard’s awful illness? Had he been a comfort she couldn’t do without after Richard’s death? Or had she been the one to offer George care in his time of need, when his marriage to Edith fell apart? Or was the real story something less noble, a matter of acting on impulses and giving in to attractions? One thing is certain: George’s wife Edith and their daughter Isabel were alive and living in a house on Inglemere Road in Mitcham, Surrey by 1918, and where they remained until Edith’s death, oddly enough in the same month and year as Grace’s – March, 1934. In contrast to Grace’s demise, fraught with tragedy and pathos, Edith’s, at the ripe age of 84, while surely sad for her unmarried daughter and companion Isabel and her Pitcher offspring, was in comparison, unremarkable and ordinary. Did Isabel send a note to her father at Rowton House, sharing the news of his wife’s death? Did George ever hear about his daughter Grace’s tragic end in the seaside resort town of Eastbourne?

George died of heart failure and a stroke on the 21st of January, 1945. The record states that he was 79, but counting from his birth in 1863 he was actually 82. The record also indicates that George’s regular place of residence was still the tiny cubicle at Rowton House in London, yet his death occurred at an address in Worthing, a coastal town only a few miles from Eastbourne. It’s tempting to think that this means something, that perhaps George was reconciled with Jennie and the remainder of her family in the end, but I’ve found nothing to substantiate the idea, and in 1945 Jennie still lived in London at Guinness Buildings. Sometime in 1954, she left London and moved in with Nellie Jane and her husband, sharing their tidy two storey rowhouse just a few blocks from the seafront. It must have seemed like a different world to her. Instead of the traffic and people noises she’d heard all her life, she’d have heard the cry of gulls and the crash of the surf. In place of the familiar smells of vehicle exhaust and sewers and other people’s cooking were the odours of fish and tangy salt water. On warm days she and Nellie Jane and Alice might have strolled the beachfront promenade, or walked out on the pier, and turned their faces to the sun. She didn’t live long after her move to Eastbourne, but it’s nice to think of her in that tranquil setting, spending her last days in the company of her daughters. Jennie died on the 19th of March, 1955, and was buried at the Ocklynge Cemetery in Eastbourne.

Sources

- Eastbourne Gazette, Wednesday, March 21, 1934

- Sunderland Echo and Shipping Gazette, Friday, July 19, 1935

- South London Chronicle, January 1, 1898

- Rogues and Vagabonds: Vagrant Underworld in Britain 1815-1985, by Lionel Rose, Routledge, Oxon, 1988

- https://www.southwarknews.co.uk/history/the-cleanest-place-to-doss-since-leaving-home/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rowton_Houses

- http://www.workhouses.org.uk/RowtonNewington/

- Down and Out in Paris and London, by George Orwell, Victor Gollancz Ltd., London, 1933

- Ancestry.ca

- Eastbourne Crematorium, Langney, Eastbourne

- Eastbourne Reference Library, Grove Road, Eastbourne

- Bexhill Library, Bexhill-on-Sea

Another featured a hand-drawn rose on its front, meticulously painted, and signed Ernest Biss. We didn’t want to soak this one for fear that the rose would disappear, so we carefully steamed it loose and watched it curl at the edges. The rose suffered a little from our efforts, and we lost some of the message on the back – but once again, it seemed disappointingly spare anyway. But we had a name, at least, and with a bit of sleuthing we discovered that Ernest was about 19 the year Doris left for Canada; he was her neighbour in College Buildings in Whitechapel, and his father was the verger at nearby St. Jude’s church, where she was baptized. Their families would have shared the same dismay when the Titanic went down, taking with it the church’s beloved minister Ernest Courtenay Carter and his wife Lilian. Doris was given the middle name Lilian for Lilian Carter; was Ernest likewise named for Ernest?

Another featured a hand-drawn rose on its front, meticulously painted, and signed Ernest Biss. We didn’t want to soak this one for fear that the rose would disappear, so we carefully steamed it loose and watched it curl at the edges. The rose suffered a little from our efforts, and we lost some of the message on the back – but once again, it seemed disappointingly spare anyway. But we had a name, at least, and with a bit of sleuthing we discovered that Ernest was about 19 the year Doris left for Canada; he was her neighbour in College Buildings in Whitechapel, and his father was the verger at nearby St. Jude’s church, where she was baptized. Their families would have shared the same dismay when the Titanic went down, taking with it the church’s beloved minister Ernest Courtenay Carter and his wife Lilian. Doris was given the middle name Lilian for Lilian Carter; was Ernest likewise named for Ernest?

♦

♦