Welcome to the world, Floyd!

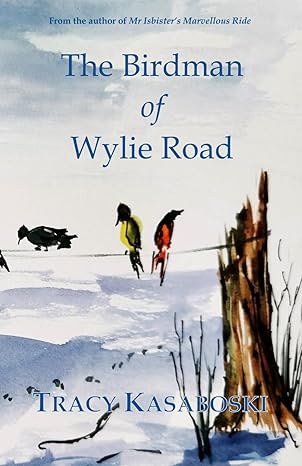

I am thrilled to share that my latest book is finished, and ready to meet the world!

The title of this one is The Birdman of Wylie Road, and if you’re familiar with the upper Ottawa Valley, you may know that the road itself, at least, is very real, even if the Birdman and the rest of the Wylie Road’s characters are completely fictional. I have had an absolute blast writing this latest book and painting it with local colour, and while the story is a product of my imagination, a writer always draws on what they know, so you can read into that what you will!

In a bit of a different twist, The Birdman is written from the point of view of the Birdman’s dog, Floyd, a perceptive and intelligent retriever whose view of the world he lives in and the people and animals he shares it with is surely one that connects us all. Here’s the blurb from the back cover.

Love, loyalty, companionship: all these things Floyd, an intuitive and observant canine, gives unconditionally to his best person, the Birdman. Over the years, Floyd and the Birdman have done it all together – bird-hunting, fishing, hiking, canoeing, camping, not to mention dancing in the kitchen and watching documentaries on tv. But these days, both man and dog are feeling their age, and despite Floyd’s best efforts to the contrary, he fears the Birdman is lonely.

When the Lady moves in up the road, Floyd does his dog-gone best to encourage her and the Birdman in their mutual interest, but pleasantries are not always the Birdman’s first inclination. Floyd begins to fear that the Birdman will end up alone despite Floyd’s well-meaning interventions, and those worries amplify when Toto Binotto, an Italian researcher and fellow bird enthusiast, becomes a long-staying guest at the Lady’s home.

With an unforgettable cast of characters both animal and human, and set against the backdrop of the Ottawa Valley with its thick forests and magnificent views of the Northern Lights, The Birdman of Wylie Road is a heart-warming tale of love, loss and lifelong devotion, told with gentle humour and the kind of insight into the complexities of the human heart that only man’s best friend could possess.

The Birdman of Wylie Road is now available in Deep River at the Valley Artisans Co-op, and will soon be available at other bricks and mortar locations throughout central and eastern Ontario such as The Tipped Ship in Elgin, and Deep River’s brand new bookstore, Saturday Morning. If you prefer to shop online, Saturday Morning can help you there too, so please try to support local when you can. If you’re truly stuck, you can also find The Birdman buried amongst almost every other published book in the world 😉 at Amazon.ca.

However you get your copy, I hope you will read and enjoy!