This is the second instalment in a series of posts that will examine how to look beyond birth, marriage, death and census records to really breathe life into one’s characters. Part 1 of the search to find out more about our somewhat randomly chosen subject, Ellen Shelley, revealed the following:

- she was an undertaker’s daughter, born in Lambeth in 1882

- she had at least 7 siblings, and her mother died when she was 17

- she had a child out of wedlock at the General Lying-In Hospital in Lambeth in 1906, when she was in her early twenties

- she was working as a waitress in a coffee shop when the 1911 census was taken

- she was still living with her father and four of her siblings at this time, but the record offers no detail about her child

The next record that turns up for Ellen Shelley confirms her Christmas Eve marriage in 1916 to a man named George Henry Smith, an electrician. Digitized records for London Church of England unions often give extra clues, and here we can see that 34-year-old Ellen, a “spinster” with middle names Priscilla Sarah, was working as a cook; that her father, by now, was deceased, and that she was living at 141 Lambeth Road at the time of her wedding. Her brothers, William Bird Shelley and Ernest Shelley, signed as witnesses, and the ceremony took place in St Mary’s parish church, Lambeth. Curiously, her 30-year-old groom was living at 13 Canterbury Place, the same address recorded as Ellen’s in the Lying-In ledger in 1906, and the address she lived at in 1911 with her father and siblings. So why, in 1916, is Ellen no longer there, and her groom George is?

Next I looked for George on the 1911 census, and despite the surname “Smith,” he was fairly easy to find, since the marriage record had given me his age, his occupation, and his father’s name. Cross-referencing a few different bits of information, I found him living at 20 Temple Street with his mother, four siblings, and a four-year-old girl named Priscilla Shelley, listed not as a member of the household, but as a “visitor.” Was this Ellen’s mystery child? And was she George’s daughter too? If so, why did they wait until 1916 — ten years after the baby’s birth — to marry?

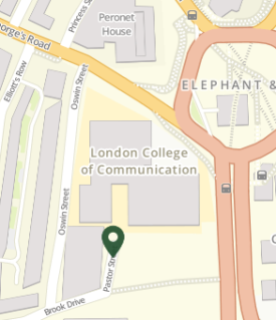

I leaped ahead, then, to the 1939 census, and found George and Ellen, nearing 60 now, living with George’s mother Jane, and also Priscilla Shelley, an assistant in a glass and china shop. Their address is 20 Pastor Street, Southwark, and the overlay of Booth’s map shows me that this is the same location as 20 Temple Street, though the name has changed. (The names Pastor and Temple must come from the street’s proximity to the Metropolitan Tabernacle, but that’s a rabbit hole for another day.)

This particular census doesn’t state people’s relationships to the head of the household, so it still doesn’t tell us whose child Priscilla was. And it’s interesting that she goes by the name of Shelley. If George was her father, wouldn’t she have carried his name after her parents married? The census does tell us she was born on July 15, 1906, a date that matches the entry in the Lying-In ledger.

So with all this added up, we can be fairly certain that, in 1906, Ellen was an unwed mother who gave birth to a baby she named Priscilla, a name that turns up often in Ellen’s ancestry. It was Ellen’s middle name, but it was also her great grandmother’s name, her grandmother’s name, and her aunt’s.

Now that we have some of the facts in place regarding Ellen Shelley, I’ll go back to her early years to try to fill things in a bit, and see if we can get a better picture of who she was.

In 1891, she is living at 62 Westminster Bridge Road with her family. The Muckells — her maternal grandmother and some of her mother’s siblings — are here with them. Next door is an actress, and a few doors down are a couple of “theatre property makers,” so perhaps there is some connection with the nearby Surrey Theatre, which put on melodramas and pantomimes during this period. Ellen’s father John, the undertaker’s assistant, probably works nearby as well, assisting in coffin-making, or taking bodies to cemeteries, or to mortuaries for coroner’s inquests.

Undertakers had a bad name in Victorian times. In Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol, the undertaker’s assistant is an unsavoury creature who snatches some of Scrooge’s belongings after his death — “a seal or two, a pencil-case, a pair of sleeve-buttons, and a brooch of no great value” — and sells them to old Joe, who runs a scavenger shop in a London slum, where:

The ways were foul and narrow; the shops and houses wretched; the people half-naked, drunken, slipshod, ugly. Alleys and archways, like so many cesspools, disgorged their offences of smell, and dirt, and life, upon the straggling streets; and the whole quarter reeked with crime, with filth, and misery.

No employer is mentioned in the documents I’ve found for Ellen’s father John, but he may have worked for the parish undertaker, who would have handled so-called “pauper funerals,” the most basic variety for the poorest of the poor, and the kind everyone strove to avoid.

At great expense, people bought burial insurance to avoid the indignity of a pauper funeral paid for by the parish; many contributed weekly to “funeral clubs” in order to save enough for decent trappings: black garments for the family, the use of a hearse and coachman, and the coffin itself – black for an adult, white for a child. Displays in undertakers’ windows advertised myriad choices available to the bereaved: elaborate funeral cards to announce deaths, plumes of black ostrich feathers for the horses pulling the hearse, stone markers carved with doves or broken lilies.

In her 1913 work Round About a Pound a Week, Maud Pember Reeves wrote that paying burial insurance was a “calamitous blunder” on the part of poor families, but understood, too, that the alternative was to settle for a pauper’s funeral paid for by poor law funds. The women Reeves interviewed as part of her indepth poverty study were from the vicinity where the Shelleys lived, and they were adamant that “the pauper funeral carries with it the pauperization of the father of the child – a humiliation which adds disgrace to the natural grief of the parents.” One woman even said she’d prefer to have the dustcart call to collect her child’s body.

A search through the British Newspaper Archive for parish undertakers turns up several pathetic stories, including mention of an ongoing problem with cheap coffins that fell apart as they were being taken to the grave. There are also stories of undertakers fined for stuffing more than one body into a coffin, or charged with not burying the bodies at all, and pocketing the fees. In my very first post on this blog, I wrote about an undertaker who claimed to have been cheated by a deceased woman’s family: he’d picked up their dead mother from the workhouse, as requested, and had intended to take her to the cemetery for burial, but the family didn’t pay him, and he claimed he couldn’t afford to pay the cemetery’s fee himself. The body was discovered on his premises when neighbours complained of an “intolerable effluvium.”

No such gruesome stories have turned up about John Shelley, but we do know that he was an undertaker in a very poor part of London, and that he would have regularly encountered grief compounded by poverty. He started working in the industry some time between 1871, when he was a boy at home with his parents, and 1878, when his occupation is listed on his marriage record. He was still working as an undertaker in 1911, a year before his death, and two of Ellen’s brothers, William Bird Shelley and Ernest Shelley (the same ones who witnessed her marriage to George Smith) were also undertaker’s assistants in 1911. So death, so to speak, was very much a part of Ellen Shelley’s life.

Next up, I’ll move ahead to Ellen’s time at the Lying-In Hospital, and the birth of Priscilla.

Fascinating! I look forward to the next installment

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s surprisingly time consuming, but fun too!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Can’t wait to see wjat happens next.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Fascinating! The illustration brought to mind the top floor rooms at Dennis Severs’ house in Spitalfields. I wondered if you’d visited when you were in London? https://www.dennissevershouse.co.uk/ Something I was told about marriage certificates is that if bride and groom are shown living at the same address it doesn’t necessarily mean they were. Apparently it cost more if you put two different addresses. This would need further investigation though!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh yes, I know the house — we had wanted to visit, and we were right in that area, but didn’t have time. The website is stunning. And yes, I’ve read the same about marriage certificates, though in this case they were different addresses: George was at Ellen’s old address, and she was at another one. I will try to puzzle out more about the various addresses mentioned in a later post. It can be very tricky because of changing street names and numbers, but the family stayed in the same general area for many years, very close to our some of our own family members.

LikeLike

Pingback: Part 3: Ellen Shelley and the Lying-In Hospital – The Cowkeeper's Wish

Pingback: Part 4: Ellen Shelley and the power of women – The Cowkeeper's Wish

Pingback: Part 5: Ellen Shelley, George Smith and the Great War – The Cowkeeper's Wish