Despite the years of research that went into creating The Cowkeeper’s Wish, we still have many unanswered questions. The brick walls rise up especially around women’s stories, for women all too often disappear behind their men. This seems particularly true of the working class. In our family, in London, England, many of the women were factory workers or cleaners or laundresses; or they did piece work like book folding or sewing at home, where they could earn a living and look after little ones at the same time. It struck us that during WW1, these were the types of women who contributed anonymously to the war effort, with little remaining now to show the part they played.

If they’d sewn clothes before the war, perhaps now they sewed any of the many parts that made up uniforms. If they’d made boots, perhaps now they made army boots. If they’d worked at a box factory, as did our grandmother’s sister, Ethel, perhaps now the boxes they made would hold ammunition, or gifts for men at the frontlines, or medical supplies. Other jobs opened up for women too — women became postal workers and bus drivers and farmers; they assisted the police and wore uniforms and blew whistles; they tended the wounded as doctors, nurses, and VADs; and they stepped up in droves to work in munitions factories.

One of our relatives married a male munitions worker in 1916. Her own occupation is not listed on the certificate, but as the 23-year-old daughter of a widowed cleaner, it’s likely she had to contribute to the household income. Did she work at the same factory as her beau? Is that how they met? No one can say now. Often the female munitions workers known about are the ones who died tragically, in an explosion or of TNT poisoning — the ones who survived are lost to history.

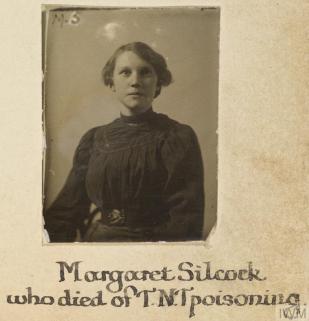

Even during the war, there was an attempt to recognize women’s contributions. Beginning in 1917, a group of women working for what would become the Imperial War Museum began gathering documentation — photographs, ephemera, written accounts — that showed the varied roles women were playing in the war. In preparation for a women’s work exhibit at the Whitechapel Art Gallery in October 1918, they wrote to the families of women who had died in service, and asked for photographs of them so that the exhibit could honour both the living and the dead. These wonderful photos remain in the IWM collection to this day, and some of the letters still exist too, and hint at the massive loss people suffered on a personal level. When 22-year-old Margaret Silcock died of trinitrotoluene (TNT) poisoning from her work at a munitions factory, her mother willingly sent a photograph, apologizing for its smallness. “It is the only one I have,” she explained, “and I can’t afford to get a bigger one as I only get 7/6 a week.”

Women like Margaret were known as Canary Girls because the explosive chemical they worked with often turned their skin yellow. Usually the effects wore off, but many died from exposure to TNT, which could cause anaemia and toxic jaundice. One of the early casualties was a young woman named Alice Post, who died in January of 1916. A newspaper reporting on the inquest into her death stated that she had begun working at a factory about five weeks before Christmas 1915, and walked a distance of 10 miles each day to get to the works and then home again. She ate well at first, but soon lost her appetite, and often complained of headaches and tiredness. The skin on her hands and forearms turned blotchy. She saw the factory’s doctor, but when she failed to get better, she was reluctant to seek medical help again — and by the time she did, it was too late. The post-mortem confirmed Alice had died from TNT poisoning, but the doctors interviewed also felt “the state of absolute tiredness” was a contributing factor, since she had such a long walk to and from work, and very little nourishment to energize her. “People in such a condition, below par, would absorb the poison very readily. The jury returned a verdict that death was due to poisoning by TNT, and added a rider that attention should be given to the washing of the overalls, and that sugar and milk should be provided with the cocoa given to the girls on their arrival at the works in the morning.”

As the war went on, safety regulations increased; but there were still fatalities, and the losses were often not the first a family had suffered. When a Welsh munitions worker named Gladys Irene Pritchard died in November 1916, the letter from the IWM’s women’s work committee must have been addressed to “Miss Pritchard,” for the response from Gladys’s sister reads:

“Please excuse me writing to say it is Mrs Pritchard and she was a widow before she died, her husband being killed on the 10th July 1916 leaving two children.”

A bit more searching reveals that Gladys Pritchard’s husband David, a private with the Welsh Regiment, was killed in action during the early days of the Battle of the Somme, and that the children, Joseph Henry and Victoria Lillian, were just five and two years old when their mother and father became two of the war’s mounting casualties.

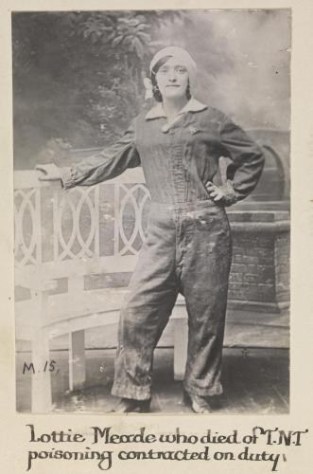

Likewise munitions worker Lottie Meade was the mother of three young ones when she died of TNT poisoning in Kensington Infirmary in October 1916. Her husband wrote to the women’s work committee that the death occurred “whilst myself was serving in France and [I] got home to late to see her alive.” The photograph he sent along for the Whitechapel exhibit shows Lottie posing proudly in her munitions coveralls; one can imagine it was a photo taken for him, and sent to the frontlines, and then brought home again, memento of a wife no longer alive. Did it surprise him to see her turned out this way, in pants and cap, making the ammunition that fed the weapons he used? How would the war have changed her future had Lottie Meade survived the poisoning? What was it like to live through a time that produced so much tragedy but also so many profound changes in women’s lives?

Lottie Meade’s death certificate lists the cause of death as: “coma due to disease of the liver, heart and kidneys consequent upon poisoning by tri nitro toluene,” and the verdict at the inquest was “death by misadventure.” An awful waste. But the picture suggests there was adventure in Lottie’s life too. The hand on the hip, the raised chin, the subtle yet confident smile — the stance of a woman making her own way in the world.

The women’s work exhibit at the Whitechapel Art Gallery opened on October 7, 1918, and by the time it ended six weeks later, 82,000 people has passed through. The most popular part of the show was the “war shrine,” dedicated to the memory of more than 500 women who’d died in some form of service.

♦

Sources:

Charlotte Meade, Lives of the First World War

Alice Post, Lives of the First World War

Gladys Irene Pritchard, Lives of the First World War

Margaret Silcock, Lives of First World War

The Silvertown Explosion, Lives of the First World War

A Closer Look at the Women’s Work Collection, Imperial War Museum

Lives of the First World War also contains 23 alphabetized “Wives and Daughters” communities as an attempt to document female deaths related to WW1.

Another wonderful story of women who served their country in ways that often ended tragically.

LikeLiked by 2 people

How brave they were, and how wonderful it is that these pictures survive as a testament to their tenacity. The music of unsung heroes.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Wonderful to hear their stories and to see the faces of these women whose lives ended far too soon. And as testament to them and the contribution they made was the 82,000 who cared to take in the exhibit and remember.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Heartbreaking stories here. I wonder what happened to their children when they died, especially in the case of both parents being absent. Perhaps a kind relative or neighbour stepped in or they may have gone to an orphanage.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Heartbreaking to read. Maybe another exhibition should be done as so many ordinary men and women’s stories have been forgotten or untold.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: The Bones & Bobbins Podcast, Season 2, Episode 11: Not So Mellow Yellow | The Bones and Bobbins Podcast