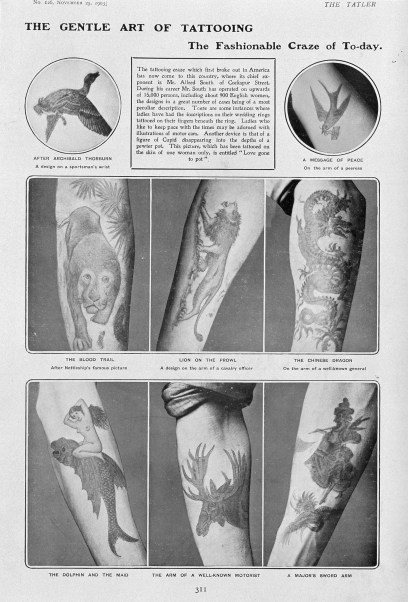

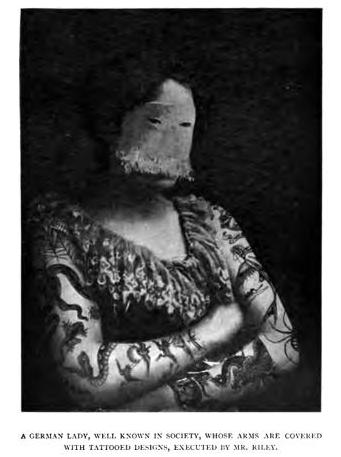

In 1903, Tatler magazine featured this spread on tattooing, “the fashionable craze of to-day.” The work was that of tattoo artist Alfred South, who claimed by that time to have inked images on no less than 15,000 people, 900 of them English women.

An emigrant to England, South was born Alfred Charles George Schmidt in Karlsbad, Bohemia, and seems to have begun using the name South some time in the 1890s, when his tattooing career began. His big break came in May of 1898, at the Royal Aquarium, an amusement palace of sorts, with tightrope walkers, high divers, human cannonballs, and hypnotists. That spring, fellow tattooist Tom Riley had to step away from his busy booth there in order to deal with what the London Evening Standard termed “trouble with his wife, who wanted to poison herself.” (Flo Riley was frequently dubbed Tom’s “Tattooed Marvel” and was “covered with many beautiful designs in seven colours.”) South stepped in and must have quickly made his mark on the tattooing scene, for according to the Standard, Riley, upon his return, was so incensed at the thought of upstart South stealing his clients that soon he began to publicly harass South in the halls of the Royal Aquarium. South pressed charges, and Riley (whose wife survived her ordeal) was ordered to keep the peace. From then on, regular newspaper ads appear for South’s services, promising “any design, all colours” — and how it must have rankled Riley that sometimes South’s ads showed alongside his own.

By 1899, though, South’s livelihood was threatened when 21-year-old Louis Montgomery Forbes died of blood poisoning shortly after South had tattooed him. Papers carried headlines about the “peculiar circumstances” around Forbes’ death, and the dangers of tattooing, and South was called to testify at a coroner’s inquest.

Forbes had come to South for tattoos on several occasions; this time he requested a lion on his chest, a procedure that took 10 hours, according to South’s testimony. Every couple of hours, South asked Forbes if he’d like a break, but Forbes always declined. While South worked with his needles, Forbes drank 14 whiskies to dull the pain, and afterwards the two went out together for a bowl of soup and then to a public house to show off the lion to a friend. They parted ways, and that was the last South saw of him.

Forbes returned to his cousin’s house, and the next day felt unwell. Fourteen whiskies might do that to a person, so perhaps he was not at first alarmed. He told his cousin about receiving the tattoo — that it had taken a long time and been quite painful, but that he didn’t attribute his illness to the procedure. A doctor was called, but he continued to grow worse. Most likely he felt dizzy and disoriented; his heart raced; his skin turned clammy and pale, and he drifted into unconsciousness. Three days after receiving the tattoo, he died. Other doctors were called in to give their opinions of the cause of his death, and while all agreed it must have been blood poisoning, none could say it had anything to do with South’s tattooing.

For his part, South claimed that by this time he’d tattooed more than 5,000 people and never had a problem. He used a fresh set of needles for each customer, and during procedures he placed them in carbolic oil. He used only the best quality Chinese ink, which he produced as part of his testimony, and offered to eat it to prove his claim, but the coroner didn’t think that necessary. “The jury reached a verdict in accordance with the medical evidence, but attached no blame to the tattooist.”

South went on with his work. As he told one reporter, “You’d be surprised to know the number of people who come to me to be tattooed. And from all classes. I’ve tattooed lords and ladies of high degree, doctors, barristers, actors and actresses, men and women of all professions, just as I have tattooed soldiers and sailors and working men. What is it that makes them want to be tattooed? Well, I suppose it’s just a fad — that’s my only explanation of it.”

In 1906, South made the news again, telling of his recent exploits in Vienna, where he’d tattooed the arm of a tiger tamer. “His conditions were that I should go inside the cage and take my design from an unfettered animal. … I had nicely arranged all my apparatus on a table inside, and was just about to begin the sitting, when, without any warning, the brute leapt at me. I stood aside, only to see my table crushed under the heavy weight of the animal. Without waiting, I rushed outside the iron door, but after a while one of the attendants told me that everything was all right again. Well, I thought that one can die only once, and re-entered the cage, and after one-and-a-half hour’s sitting I had accomplished my task.”

Over the years what seems to have changed most was the kind of tattoo people desired. By January 1914, South was offering “your favourite horse, dog or cat tattooed upon your arm, neck, shoulder or ankle.” The Daily Mirror carried an image of him at work on a client. South sits in his lab coat, a dowdy, balding, somewhat round man who resembles Alfred Hitchcock. He holds his needle against a woman’s arm; she’s watching him work, and smiling a little tentatively, but South’s eyes study the dog she holds — a fluffy white lap dog — who in turns stares out at the camera with a seemingly baffled expression.

When war erupted later that year, two of South’s sons enlisted, surely thankful their father had long ago stopped using Schmidt as a surname. The younger son’s involvement was brief — just 18 and a Boy 1st Class on board the ship Edward VII, he was blown overboard in a gale and lost to the sea. His record shows his initials, LS, were tattooed on his upper left arm; the work of his father, perhaps — but simple and understated compared to Louis Forbes and the Tattooed Marvel.

Tattoos had long been popular among soldiers and sailors. In the box for “Wounds, Scars, Marks &c.,” service records note a plethora of horseshoes, crosses, women’s names, clusters of forget-me-nots, anchors, snakes, birds, and shamrocks. By 1915, women and girls — “who in ordinary times would not dream of being tattooed” — were coming to South wanting tattoos to remind them of a man who had gone off fighting. “The usual request is for a regimental badge to be etched on their arms, sometimes with the words ‘I love’ or ‘Yours forever.'”

Curiously, the desire for these “indelible mementoes” was something that seems to have puzzled him over the years. He regularly fulfilled requests for sweethearts who wanted each other’s portrait tattooed. But he mused, “it’s a bit awkward if they both should happen to change.” One can imagine him shrugging and simply carrying on. By the time of the First World War, South had been tattooing for some 20 years, and must have marveled that “the fashionable craze of to-day” was also the craze of tomorrow, of the next day, and the day after that.

♦

Sources

- “The Gentle Art of Tattooing.” Tatler, November 1903 (Wellcome Library).

- Naturalisation Certificate: Alfred Charles George Schmidt. 28 February, 1905. National Archives.

- “Police Intelligence — Westminster.” London Evening Standard, 16 July, 1898.

- “Pictures on the Skin: The Experiences of a Society Tattoo Artist” by Pat Brooklyn. English Illustrated Magazine, 1903.

- “Wanted … Flo Riley.” The Era, 11 March, 1899.

- “The Showman.” Music Hall and Theatre Review, 5 December, 1902.

- “Singular Death of a Young Man at Cookham.” Reading Mercury, 8 April, 1899.

- “Died After Being Tattooed — A Mysterious Death.” Eastern Evening News, 6 April, 1899.

- “Tattooing Among the Aristocracy.” Nottingham Journal, 7 April, 1899.

- “Tatooist’s Exciting Adventure.” Belfast News-Letter, 17 April, 1906.

- “Dogs’ Portraits Tattooed on the Arm.” Daily Mirror, 17 January, 1914.

- “Tattooed Women.” Daily Mirror, 14 October, 1915.

- Lives of the First World War: Leslie South formerly Schmidt