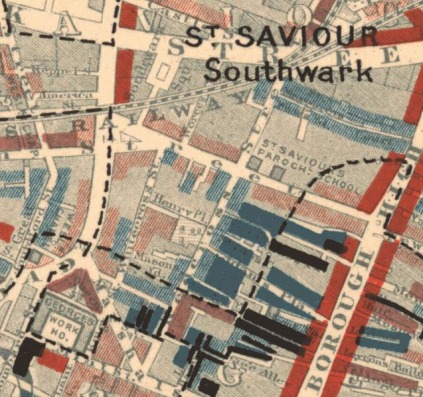

Much of The Cowkeeper’s Wish takes place in Red Cross Street, now Redcross Way, in what was then a poor neighbourhood in London, England, just south of the Thames. Our family lived in the street from the 1840s to the early 1900s, and was well acquainted with the workhouse nearby. Our great-great grandmother, Mary Jones Evans, moved in after her husband died, ostensibly because she was too lazy to take care of herself now that he was gone.

That’s the story that has filtered down over the years, but surely the true reason was more complicated. The anecdote nonetheless reveals the disdain people often felt — feel! — for those in need of a helping hand. Many so-called “inmates” of the workhouse were women much like Mary: poor, aging, and widowed, with few options for bettering their lives.

She was there in March of 1897 when Elizabeth Legge, a Scottish woman in her mid-forties, committed suicide. Elizabeth was employed as a workhouse midwife, and was also a widow, though of better means than our Mary, it would seem. Her husband had been a doctor, according to inquest testimony, and since his death she’d worked at a number of Scottish hospitals, and come to the workhouse late in 1896. She’d paid to have a uniform made, and had been engaged for some four months as a midwifery nurse, but didn’t enjoy the job and complained to her friend, a clerk named Arthur French, that not only was she herself treated shoddily, she abhorred the way her co-workers treated the inmates.

“She said she did not like the conversation … which was always about sending inmates to prison who did not behave themselves. She did not like to hear that sort of thing and she very often left the table in consequence of such conversation going on.”

The workhouse master wasn’t happy with her either, and in March she was given her notice, and asked to return her uniform. This she thought grossly unfair, according to French, since she had paid to have the uniform made.

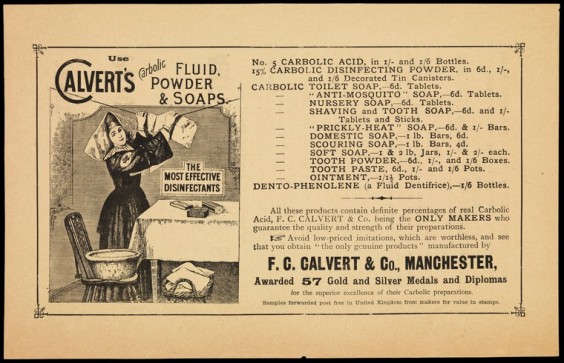

Another witness — an inmate named Mary Ann Prater, who like the midwife and our great-great grandmother was a mid-forties widow — testified that she brought a cup of tea to Elizabeth’s room at about 7:25 one morning, and when she turned to fetch a spoon and some sugar, Elizabeth called out “Goodbye, Prater!” and began to swig from a bottle of carbolic acid she’d had hidden in her bed.

The workhouse porter was called, and tried to administer mustard water. He could hear “a gurgling noise” in her throat, and “sent messengers in all directions for doctors.” Two came immediately that morning, and pumped her stomach. But it was not until 5 o’clock that evening that she was sent to nearby Guy’s Hospital, and the article doesn’t specify how she fared during the day, or why there was such a delay in admitting her.

The use of carbolic acid for suicide was prevalent in the 1890s, especially among women, since the substance was easily obtainable “from any huscksterer, oilman or druggist,” according to the Lancet medical journal. It had been used as an antiseptic since the 1860s, and the role it played in “self murders” had steadily risen. By now, doctors had seen so many of these types of “painful and cruel” deaths that there were calls to label carbolic acid a poison “put aside from general use and only employed by skilled hands or under professional direction.” Of course, with those stipulations, midwife Elizabeth Legge would still have had access.

“I am house physician at Guy’s Hospital,” Dr. Wilson Tyson testified. “I saw deceased directly after her admission. … She was conscious, but in a state of collapse. The limbs were curled, the pulse was rapid and feeble, and she was breathing rapidly. She said she had taken carbolic acid. An antidote was given her, but it had no visible effect. Deceased died at 7:15 in the evening” — no doubt a distressing 12 hours from the time she first swallowed the acid. “I asked her why she took the poison, and she said she did not know.”

Mary Ann Prater said that Elizabeth had been “very strange in her manner for the last five or six weeks. I and the other women noticed it. We thought she was not altogether in a sound state of mind the last week. She seemed to ‘give way’ and to be overexcited.” In answer to Arthur French’s suggestion that Elizabeth had been upset about the way she and others were treated at the workhouse, Prater said she’d never heard her complain, and that she hadn’t cared at all about giving up the uniform.

So what was true? Why would French say she had cared if she hadn’t? Would Prater have been instructed, or even just urged, by the workhouse master to downplay the reason for Elizabeth’s unhappiness? There’s no way to know the real story now, but all of the articles about Elizabeth’s death mention the uniform, and the fact that she was out of work. Did she fear what would become of her now that she’d lost her job and had no uniform to bring to the next potential place of employment? Did she have so little money that the cost of having a new uniform made was beyond her reach? Far from Scotland, with no relatives, no husband, and few friends, did she fear the workhouse would be home from now on, into her old age, as it was for Mary Jones Evans and Mary Ann Prater? The South London Chronicle hints that there was more to the story, but it is long gone now.

“The Coroner said he would like to mention publicly that there were witnesses present who could show that the deceased was in difficulties, which was one additional reason why she committed the act; but no purpose would be served by going into that.” A strange decision — though technically a coroner’s inquest was held to determine the cause of death, and the reason (if infinitely more interesting) was perhaps less important.

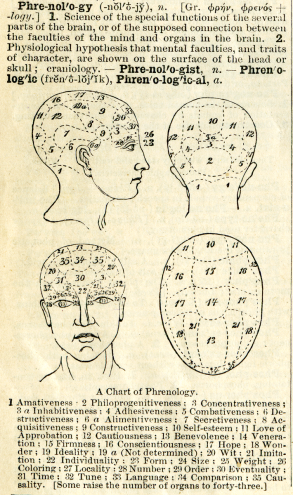

At least one of the jurymen, however, was curious about reason, and offered up his own theory. He was familiar with phrenology, which linked specific areas of the brain with character and mental ability. It had been a popular concept in Britain in the early Victorian years, and though it had long been discredited as a scientific theory, it still had pockets of followers in the 1890s. The “phrenological juror” had seen Elizabeth’s body in the mortuary, and noticed that the “organ of sensitiveness” was well developed; such people, he believed, would be sensitive to things ordinary people would not observe. “People ought to be very careful what they say to such persons.” In his opinion, Elizabeth Legge’s “vitativeness” was entirely absent, which meant she had no “want of life.” His comments evoked nothing more than laughter, and a mocking “Oh! Ah! Yes!” from the coroner, an educated man who likely had no time for pseudomedicine.

The jury returned the vague but all too common verdict of “Suicide whilst temporarily insane,” and Elizabeth Legge, compassionate widowed midwife, was heard of no more.

♦

Sources

- “Southwark Nurse’s Sad Suicide.” South London Chronicle, 27 March, 1897.

- “The Fatal Record of Carbolic Acid.” Alfred Edwin Harris, The Lancet, 28 November, 1896.

- “Suicide of a Dundee Doctor’s Widow.” Dundee Courier, 25 March, 1897.