“It seems a person is in danger wherever he is.”

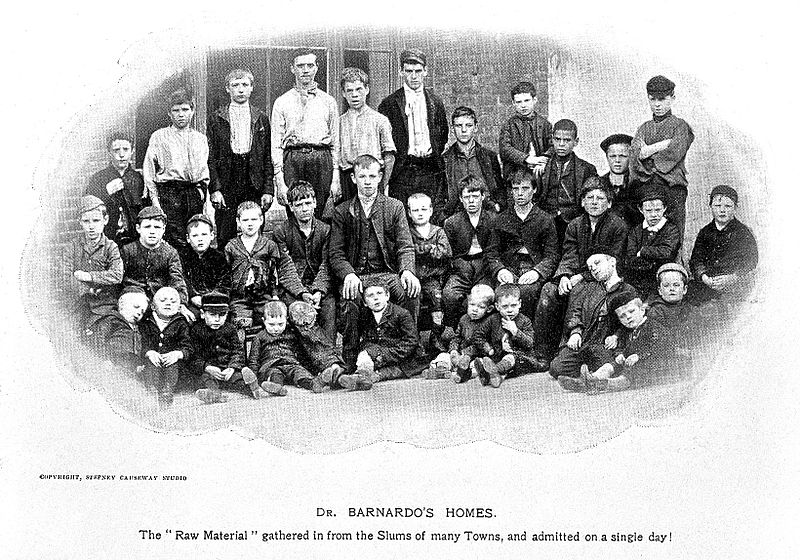

Last time, I told you about the early years of Hugh Willis Russell, who came to Canada at age 11 with the Barnardo’s organization, and landed in Wingham, Ontario, only to cross the ocean again in 1915 as a soldier. In January 1916, in a letter to young Graham Wray, the son of the farmer Hugh worked for, Hugh claimed war was “a great life,” and that soon he’d be able to “kill a lot of Germans.” But his enthusiasm for war quickly diminished.

It’s interesting to note that when Hugh first enlisted, he was described as having no distinguishing marks or tattoos, but at some point overseas, he had a horse’s head and a horseshoe tattooed on his forearm. His love of horses is evident in his letters home to Graham, some of which were published in the Wingham Advance. In February 1916, from “Somewhere in Belgium,” he writes:

I am longing for a pair of horses to drive. I think I will see my CO and ask him if I can transfer into some unit where I can get a horse to look after. I always had a great fancy for Judy, and I used to take a great interest in her, and paid the best attention to her care and comfort. You never knew how sorry I was the day your father took her out of the gate for the last time. If I ever see her again I will be tempted to buy her. I think she would know me. … Well, I had better quit, or else I will be thinking there is no war on, and I am back in Canada trading horses.

From your old friend, Hugh

PS — Here is a song we sing in the trenches: Sing me to sleep where the bullets fall; let me forget the war and all. Damp is my dug-out, cold are my feet, waiting for someone to sing me to sleep.

For a horse-lover especially, it must have been dismaying to see up close what war did to these animals. Millions of horses were requisitioned for war work. They were lifted by cranes onto ships that carried them across the ocean. Sometimes they didn’t survive that terrifying journey. Those that made it were used in cavalry charges, or to transport messengers, supplies or equipment, or pull heavy artillery and loads of wounded. Large and vulnerable, truly beasts of burden, they perished in mind-boggling numbers – some sources say eight million died in battle, at sea, or of illness, disease, exhaustion, or poison gas. One soldier wrote that horses, too, suffered trauma, and would sometimes “shiver, tremble all over, and break out in a sweat” when the shelling started. Seeing horses injured was “worse than seeing men cut up. The men have an idea what it is all about but the horses have to take it as it comes and say nothing.”

In March, Hugh wrote to Graham:

Well that was quite an accident you had while you were on your way to bid farewell to your old neighbours, I am glad to hear you both got off safely. It was certainly a good thing that you didn’t have [the horse] Pete, or I am afraid it would have been the worst for you. It seems a person is in danger wherever he is. You make me homesick when you speak of dealing horses and cattle and of someone getting married. I often dream I am back there working at one thing or other, and it all seems real, and I forget there ever was a war until a big gun firing or mine blowing up awakens me, and I remember I am still here in Flanders and the enemy is still there. … Well I guess this is all I can say this time, hoping to see you all soon. I will say good-bye.

Your loving friend, Hugh

In August, another letter arrived, saying “we have been up against it pretty hard this last three months,” but “I am getting used to these Belgian horrors now.” Even the time out of the trenches was gruelling, he told Graham, “for they keep drilling us all the time.” But he got great joy out of a horse show put on for the men a few days before writing. “Just think,” he wrote with wonder, “a real horse show within range of the German guns,” and went on to describe the events and the prizes in detail. There was “a Charlie Chaplin” in the ring too — presumably someone impersonating the popular star, and who brought some much-needed comic relief. He closed the letter with his regular refrain, “so hoping to see you all some day soon,” and included a drawing from the trenches, which unfortunately was not reproduced for readers of the Wingham Advance.

Together the letters from Hugh to Graham form a picture of a bright, thoughtful, articulate young man who’d developed close attachments not just to the family who’d taken him in, but to his wider community of Turnberry and Wingham in Huron County. So it’s no surprise that in September, during the Battle of the Somme, the paper reported “Turnberry Boy Falls,” as though Hugh was one of their own.

Word was received here that Pte. Hugh W. Russell 54180 had been admitted to 2nd Western General Hospital, Bristol, England, suffering from severe shell shock. Hugh had made his home for some time with Mr. and Mrs. Jas. Wray, 6th con. of Turnberry and no parents could be kinder or think more of him. He went to London from Wingham on Feb. 1st, 1915, and enlisted with the 18th Batt. … At the time he was wounded he had served over a year in the trenches. … Hugh was well liked by a wide circle of friends who hope he may recover and come back to old Huron again.

Hugh’s case was indeed severe. His record shows that he was unconscious for three days, and when he woke, he couldn’t speak or walk. He was invalided to England, where the doctors had a low opinion of his overall intelligence, which seems at odds with his letters and must have been due to his trauma. He received various forms of treatment to help him regain his speech, but the words didn’t come.

According to the British psychiatrist Frederick Mott, the treatment for mutism from shell shock was often quick and simple. “The patient, after a careful and thorough examination, is assured that he will be cured of his disability. … he is asked to produce sounds, to cough, to whistle, to say the vowel sounds, which he will probably not be able to do. The voice may return by suggestion only. But a more rapid method is to reinforce suggestion by the application of the faradic current to the neck by means of a roller electrode or brush. The current is increased in strength and very often the patient immediately recovers his voice and speaks.”

Early notes from Hugh’s time at a hospital in Bristol suggest that these methods were attempted, and eventually he could walk again, and whistle “a trifle,” and place his lips into the shapes necessary to form sounds. But though he understood all that was said to him, he shook his head when asked to speak. “Lies half asleep most of the time – is not anxious to communicate with anyone.” He had ferocious headaches and insomnia, and then nightmares when he did manage to sleep. Notes in his file show that treatment included anaesthesia, hypnotism, and electric shock therapy, but that there was “no effect except to terrify him.”

Theories varied as to what was at the root of these men’s troubles, and changed over time. Were their symptoms a result of a physical shock to the system brought on by heavy bombardment – a “sudden jarring of the mental machinery,” as the nurse Dora Vine put it? Or were these men of cowardly, weak stock to begin with, and so made poor soldiers? Or were they suffering mental trauma from prolonged exposure to stressful conditions? Approaches to curing them ranged from gentle and nurturing to shockingly harsh, and doctors often disagreed with each other about what patients needed. Canadian psychiatrist Lewis Yealland, working in England during the war, described electricity as “the great sheet anchor” in cases of mutism, and claimed a 100-percent success rate. In his 1918 book Hysterical Disorders of Warfare, he laid out the case of a 24-year-old patient who’d been mute for nine months.

Many attempts had been made to cure him. He had been strapped down in a chair for twenty minutes at a time, then strong electricity was applied to his neck and throat; lighted cigarette ends had been applied to the tip of his tongue and ‘hot plates’ had been placed at the back of his mouth. Hypnotism had been tried. But all these methods proved to be unsuccessful in restoring his voice. When I asked him if he wished to be cured he smiled indifferently. I said to him: ‘… You appear to me to be very indifferent, but that will not do in times such as these.’ … In the evening he was taken to the electrical room, the blinds drawn, the lights turned out, and the doors leading into the room were locked and the keys removed. The only light perceptible was that from the resistance bulbs of the battery. Placing the pad electrode on the lumbar spines and attaching the long pharyngeal electrode, I said to him, ‘You will not leave this room until you are talking as well as you ever did; no, not before.’ The mouth was kept open by means of a tongue depressor; a strong faradic current was applied to the posterior wall of the pharynx, and with this stimulus he jumped backwards, detaching the wires from the battery. ‘Remember, you must behave as becomes the hero I expect you to be,’ I said. ‘A man who has gone through so many battles should have better control of himself.’ Then I placed him in a position from which he could not release himself and repeated, ‘You must talk before you leave me.’ A weaker faradic current was then applied more or less continuously, during which time I kept repeating, ‘Nod to me when you are ready to attempt to speak.’ This current was persevered with for one hour with as few intervals as were necessary, and at the end of that time he could whisper ‘ah.’ With this return of speech I said: ‘Do you realise that there is already an improvement? … You will believe me when I tell you that you will be talking before long.’ I continued with the use of electricity for half an hour longer, and during that time I constantly persuaded him to say ‘ah, bah, cah,’ but ‘ah’ was only repeated. It was difficult for me to keep his attention, as he was becoming tired; and unless I was constantly commanding him his head would nod and his eyes close. To overcome this I ordered him to walk up and down the room, and as I walked with him urged him to repeat the vowel sounds. At one time when he became sulky and discouraged he made an attempt to leave the room, but his hopes were frustrated by my saying to him, ‘Such an idea as leaving me now is most ridiculous; you cannot leave the room, the doors are locked and the keys are in my pocket. You will leave when you are cured, remember, not before.’

As the treatment went on, the patient wept and finally whispered for water, which was denied until a louder sound could be made, brought about by the use of a stronger current. “I don’t want to hurt you,” Yealland’s recounting goes, “but, if necessary, I must.” After four hours’ continuous treatment, the man was deemed cured.

It’s impossible to know the specifics of Hugh Russell’s treatment now, and one can only hope he endured nothing as horrible as the case above. By the time he was moved to another hospital in February 1917, he was still not speaking, but gradually he began to improve in other ways. He slept and ate well, and began “regaining confidence,” though he still had headaches and nightmares. “Is now employed about the stables,” a doctor wrote in April. “General condition is good. His general nervousness and fear of MO’s is disappearing.” As an aside, presumably to explain the fear of medical officers, the doctor added, “(He was frightened of former methods to) …” but the sentence is unfinished, and the following page, if there was one, is missing from Hugh’s file. “Has been to several horse races,” the doctor wrote a month later. “Did not speak even under excitement.”

Whatever happened to Hugh with the aim of curing him, he wanted no more of it. When he arrived back in Canada in the summer of 1917 and entered the mental hospital in Cobourg – an asylum taken over for military purposes – his picture appeared in the Wingham Advance, surely submitted by the Wrays. “As soon as was possible,” the paper reported, “he received a week’s leave in order to visit with Mr. and Mrs. Jas. Wray …, with whom he made his home before enlisting. They have been all to him that parents could be to any boy.” He stayed at Cobourg until December, silent all the while. “At present his only trouble is complete loss of voice,” the doctor there wrote, “and he refuses any treatment for this, says he was tortured enough in England by treatment. … This man is anxious for his discharge. … He should pass under his own control.”

And so Hugh was discharged from the army and left to pick up the pieces of his life. In the next post, I’ll try to put together what happened to him in the ensuing years, leading up the 1930s when he disappeared from the farm he was working on. I’ll also touch a little more on his brother and sister, Barnardo’s kids too, and whether the siblings stayed in touch with one another over the years.

❤

Oddly, it seems to me, the world has gone mad for toilet paper. Almost as soon as schools and businesses began to close in reaction to the threat of Covid-19, and “social distancing” became a familiar term and practice, toilet paper disappeared from store shelves. I don’t know why that happened; I assume there are people somewhere who have reams of the stuff in their basements, secure in the knowledge that no matter what Armageddon might come, they at least will be able to wipe their bums.

Oddly, it seems to me, the world has gone mad for toilet paper. Almost as soon as schools and businesses began to close in reaction to the threat of Covid-19, and “social distancing” became a familiar term and practice, toilet paper disappeared from store shelves. I don’t know why that happened; I assume there are people somewhere who have reams of the stuff in their basements, secure in the knowledge that no matter what Armageddon might come, they at least will be able to wipe their bums.

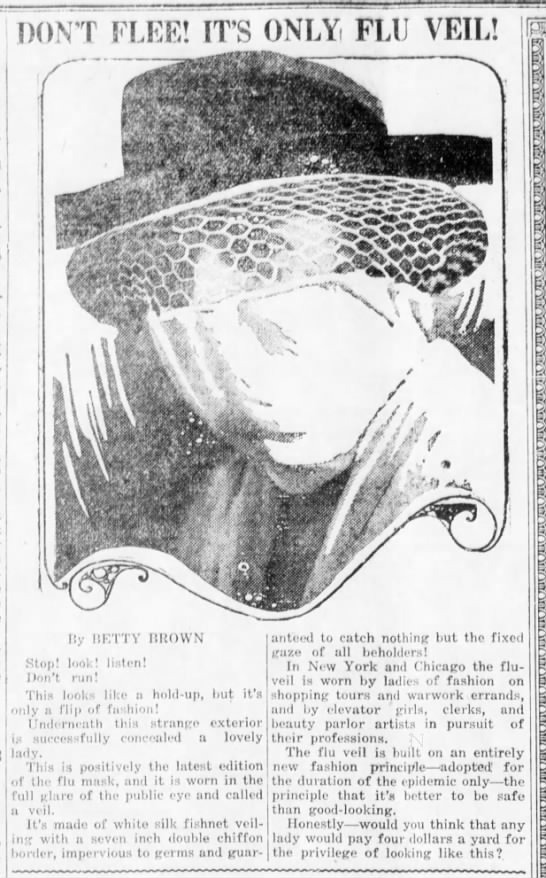

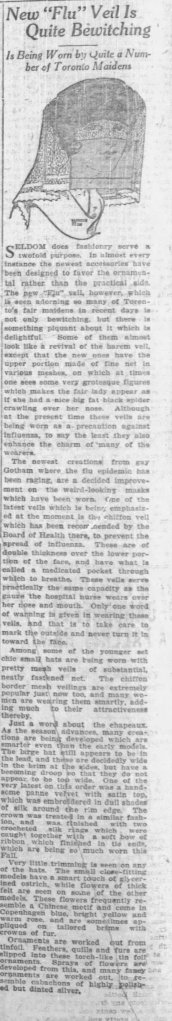

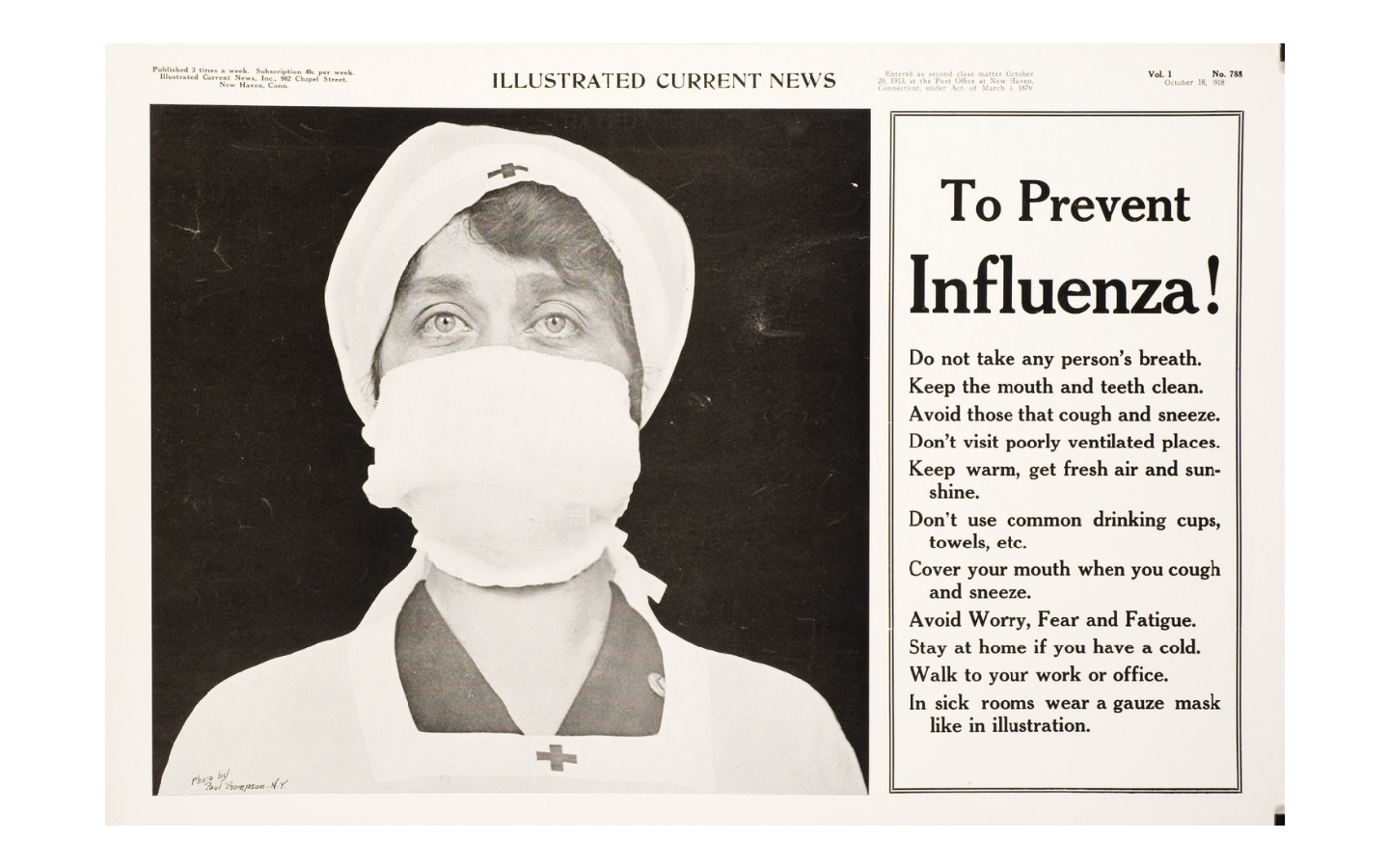

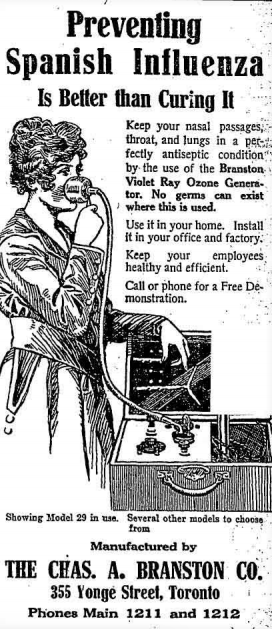

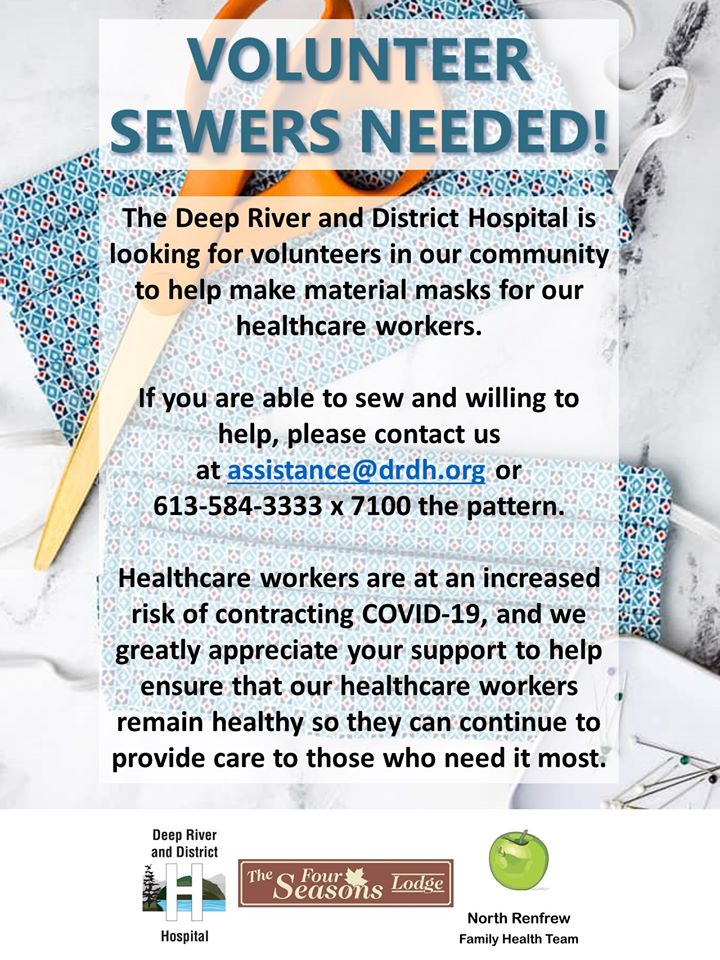

Elsewhere, similar efforts are ongoing. My sister wrote from Toronto about a friend who has turned her talents as a seamstress (she owns a yoga clothing company called Dear Lil’ Devas) to making masks. My other sister wrote from Peterborough about a woman she knows who works from home as an energy and sustainability analyst for architects and building planners, but who has broken out the needle and thread and started stitching face masks.

Elsewhere, similar efforts are ongoing. My sister wrote from Toronto about a friend who has turned her talents as a seamstress (she owns a yoga clothing company called Dear Lil’ Devas) to making masks. My other sister wrote from Peterborough about a woman she knows who works from home as an energy and sustainability analyst for architects and building planners, but who has broken out the needle and thread and started stitching face masks.