I’ve mentioned before that I’m currently working on a new book about WW1 soldiers and medical staff returning to Canada after the war. The book is non-fiction, though not family-related this time, however the research chops Tracy and I acquired writing The Cowkeeper’s Wish have come in extremely handy for this new project. Sometimes the stories are so fascinating I go down rabbit holes and disappear for great lengths of time.

So it went when I came across an article about a man named Hugh Russell. I was on a mission to find out more about shell shock — what we would now call PTSD — and how men grappled with it for years after the war was over. In a newspaper archive, I found a 1937 article about a veteran having gone missing from the farm he was working on near Wingham, Ontario. The Windsor Star reported:

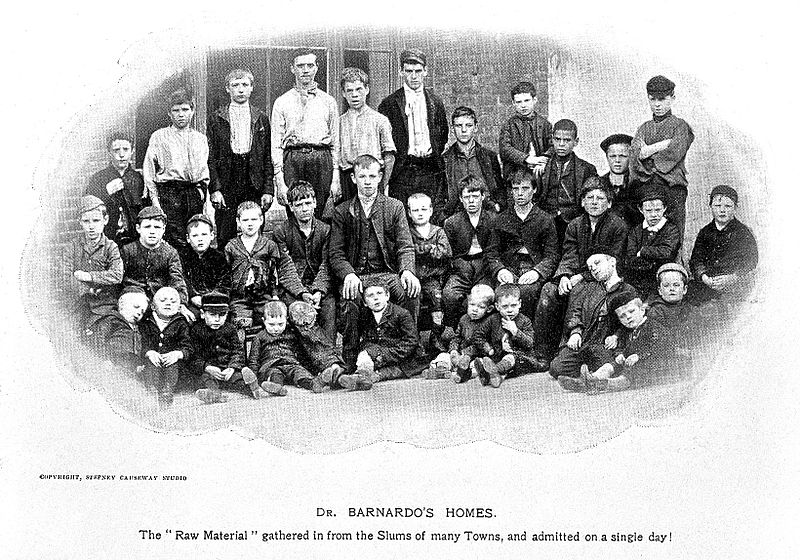

Fear that Hugh Russell, 42-year-old farmhand and returned soldier, is lost in a treacherous swamp in what is known here as the Alps, is being entertained here today. Russell was said to have been acting strangely when he disappeared from the home of his employer, Nelson Pickells, Sunday night, and when he did not return to his work yesterday morning, a search of the swamp in the vicinity of the Pickells farm showed he had slept in the swamp overnight. It is feared he may be suffering a recurrence of shell shock. The farm is on the Alps in the Township of Culross, in a district where there is particularly treacherous land with many morasses and bog holes. Russell, a former Barnardo Home boy, and said to have suffered shell shock during the war, came to work for Nelson Pickells last Christmas. He ate his dinner on Sunday night but, it is reported, acted in a strange manner and without any comment left after the meal for the swamp. The Pickells believed he was suffering melancholia, and did not worry until he failed to return. He is about five feet six inches tall, has jet black hair, a swarthy complexion, and is very thin. When he disappeared he was wearing a white helmet, dark overalls, a dark blue shirt and horn-rimmed spectacles.

The article made me curious to know more about Hugh Russell — his childhood as a “Barnardo boy,” his war experience, what treatment he might have had for shell shock, and how he’d reintegrated into society after the war. Of course I also wanted to know if he made it out of the swamp! So I started digging, and was quite amazed by the amount and the variety of material I found, sometimes with the help of strangers with a shared curiosity, sometimes from creative and persistent searching. Each piece fitted into another piece and added context to what was already there. I could write a whole series of posts explaining how these pieces emerged in a non-linear way, and how the genealogical sleuthing unfolded. But Hugh’s story is so touching that I think I’ll just tell it as I know it now, in chronological order.

Though his service record says he was born in March of 1895, Hugh Willis (elsewhere William) Russell was actually born on September 27, 1894, in Belfast, so perhaps he didn’t know his birthday. He was the eldest child of Thomas John Russell, a coppersmith, and Sarah Neeson, a weaver, who’d been married a year earlier. A few years later, they had a daughter, Ethel Baker Russell. The family lived at various addresses in Belfast in the 1890s, but by 1899, they’d moved to Birkenhead, Cheshire, a seaport town that looks across the River Mersey to Liverpool. There, a son named Robert George was born. The baptism record shows that Thomas was still a copper/tinsmith, as does the 1901 census record, which puts the family on Back St. Anne Street.

I’m still not certain what happened to Thomas and Sarah (though I have plenty of hunches!), but by 1906, Hugh was on his way to Canada in the care of Barnardo’s. Thomas John Barnardo was the founder and director of homes that took in poor children, beginning in the 1860s. For a glimpse of his philosophy, see his own book, Something Attempted, Something Done!

For those unfamiliar with the home child scheme in general, Library and Archives Canada puts it this way:

Between 1869 and the late 1930s, over 100,000 juvenile migrants were sent to Canada from the British Isles during the child emigration movement. Motivated by social and economic forces, churches and philanthropic organizations sent orphaned, abandoned and pauper children to Canada. Many believed that these children would have a better chance for a healthy, moral life in rural Canada, where families welcomed them as a source of cheap farm labour and domestic help.

After arriving by ship, the children were sent to distributing and receiving homes, such as Fairknowe in Brockville, and then sent on to farmers in the area. Although many of the children were poorly treated and abused, others experienced a better life and job opportunities here than if they had remained in the urban slums of England. Many served with the Canadian and British Forces during both World Wars.

In the LAC’s Home Children database, I found Hugh, age 11, arriving on board the Dominion with 240 other children heading to uncertain futures in a foreign land. Many home children had horrible experiences. Even those who weren’t mistreated must have been devastated to leave their families at such a young age. As I mentioned in another post about a home child, many of these young men were among the first to enlist in WW1, in the hopes that they could get back to England to see their families again. (In 1908, Hugh’s sister Ethel arrived and was placed with a family in Orangeville; and in 1912, Robert came too, and went to Bolton. Like their brother, they’d come with the Barnardo’s organization. Why, and whether there were other children, I’m still not sure.)

Hugh was placed in Wingham, Ontario, with farmer James Wray and his wife, Martha, who had a little boy named Graham. James Wray kept horses, and it seems that Hugh developed a great love for them over the years. In various places, his service record labels him a horse trainer, trader and jockey. When he enlisted with the 18th Battalion in London in February 1915, he was still living with the Wrays. Graham would have been about 12 by then, and would not have remembered a time when Hugh wasn’t part of the household. Hugh’s service record describes him as 5’3″, fair-skinned, with blue eyes and dark brown hair. He had no distinctive marks or tattoos, and described his trade as “farmer.”

By April of 1915 he was on board the SS Grampian, heading back across the ocean, nine years after his arrival with Barnardo’s. He would have heard news, around this time, of the Battle of Ypres, and the Germans’ first use of poison gas to attack the enemy. Soon, gas masks were part of a soldier’s essential equipment, and a horse’s too.

A little of what Hugh experienced on the Western Front comes through in his letters home to Graham, which were occasionally published in the Wingham Advance. On January 2, 1916, from “Somewhere in Belgium,” he wrote:

Dear Graham … Well, it is still raining and the mud is getting deeper, I would much rather have the snow. It is certainly miserable with your feet wet all the time and we are all the time scraping off mud. But there is a good time coming and so we are trying to be cheerful until it comes. I don’t believe we will have another winter out here, I think there will be something doing in the spring. You see we can’t do much as there is so much mud and water. I am in the machine gun section now so I will likely have a chance to kill lots of Germans.

I suppose you had as merry a Christmas as ever, we were in the trenches that day, there was no firing and everything was quiet. We invited the Germans over to dinner, some of them started out but got scared before they got far and beat it back. We can [call out] to them and hear them answer but we can’t understand them. I think they are Prussians in front of us. They pump the water out of their trenches and it runs down into ours, so we have to keep pumping all the time. We have a bit time with the rats in this country they seem to be here in millions. They are all sizes and colours, sometimes when they jump up on the parapet they startle us for they look like a man coming over. They are very tame and we have to kick them out of the way, they often eat our rations and keep scratching and running about when we are trying to get to sleep and I guess they bother the Germans just the same.

This is a great life. After this I will be able to live back in the bush in a hole in the ground, I’ll hardly feel comfortable in a feather bed. I just get my clothes off every eighteen days that is to get a bath. Still we don’t mind it much and we have many a good laugh, you would think if you heard us sometimes that there was no war on at all. I don’t believe I could stay away from the boys very long now, we are so attached to each other although the old battalion is gradually changing into a different lot of faces. The half of them seem to be strangers to me now.

Well I guess when this is all this time. When you write again send my letter to machine gun section instead of B company. Hoping this year will see us all together again, I remain your old friend.

Hugh

The tone of Hugh’s letters changed as the months went on, and by September 1916, during the Battle of the Somme, Hugh was in no condition to write. But I’ll save that part of the story for next time, exploring Hugh’s war experience in more detail, as well as his love for horses, and his treatment in England for shell shock.

❤

With thanks to the London & Middlesex Branch of Ontario Ancestors’ facebook group, and in particular the tenacity of Cookie Foster. Appreciation also for the Huron County Museum’s wonderful collection of digitized newspapers, and Eric Edwards’ tireless 18th Battalion research. And with special thanks to Wray family descendants.

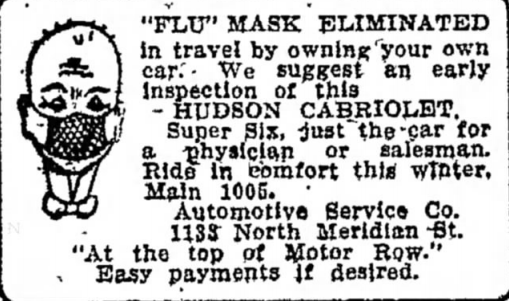

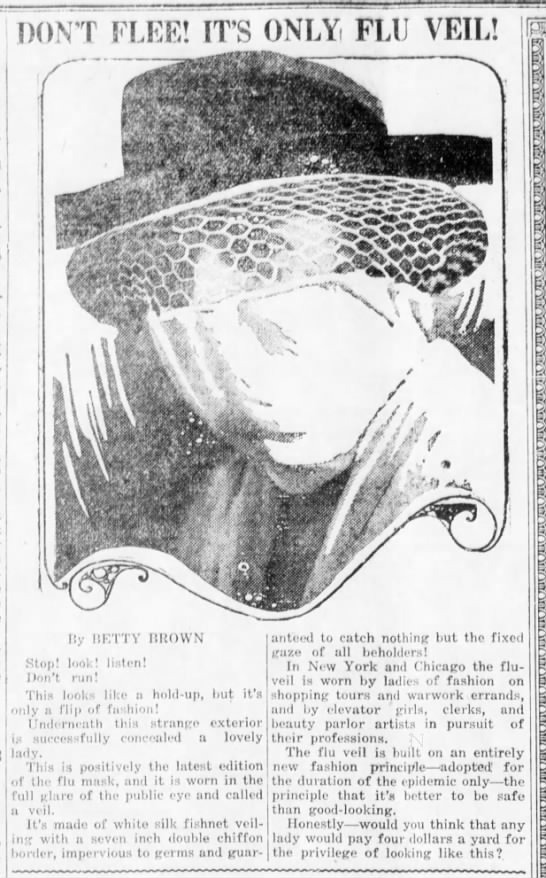

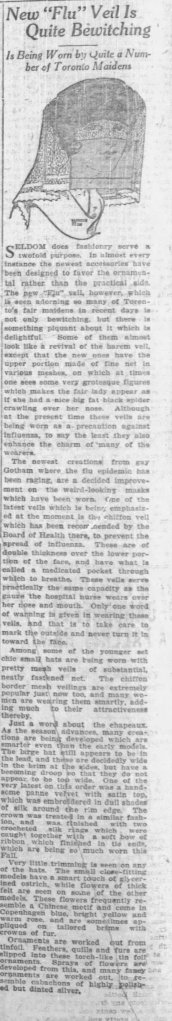

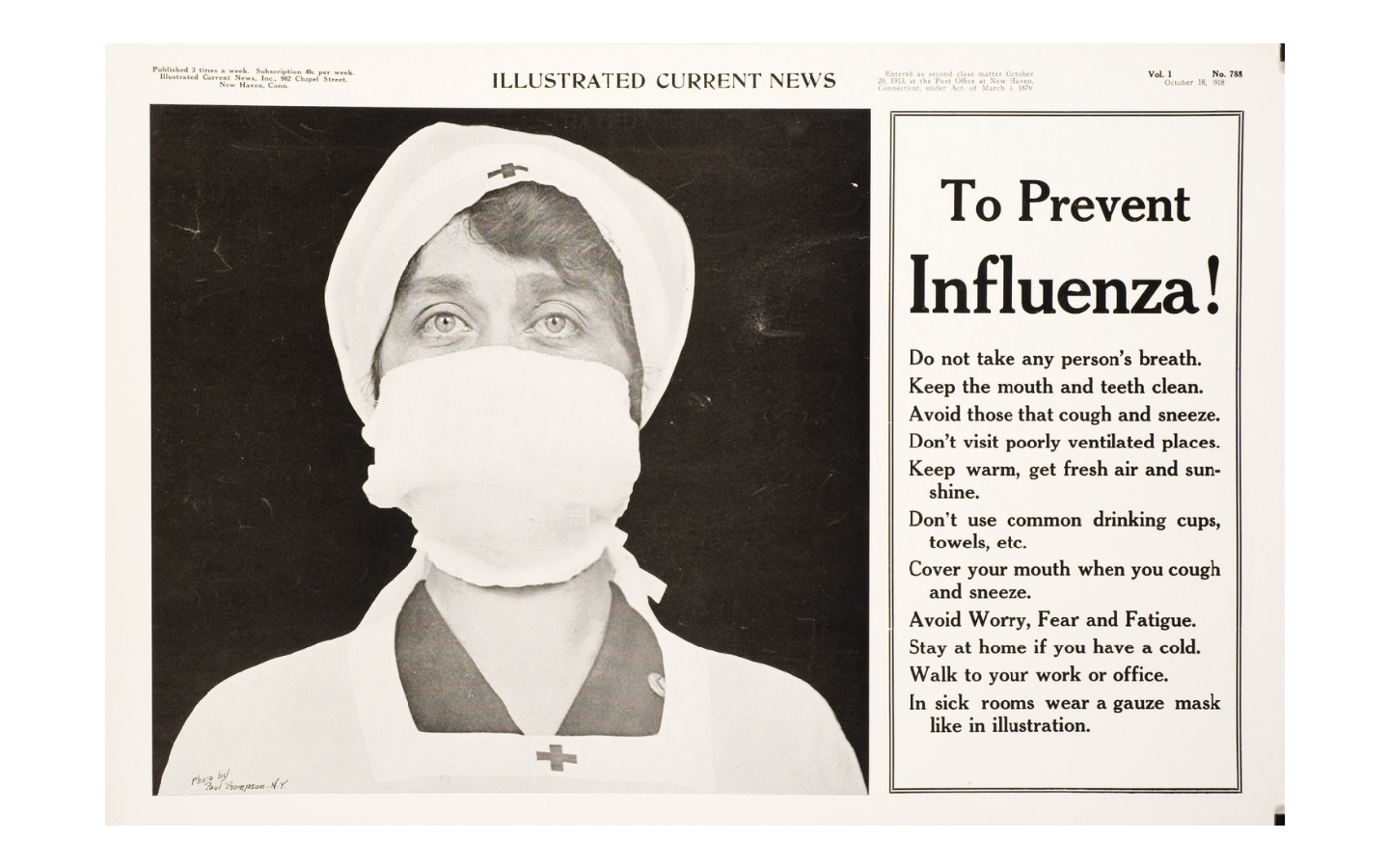

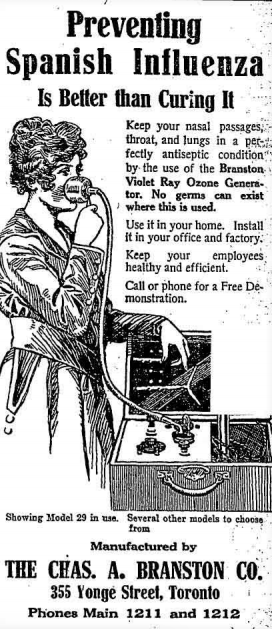

The flu carried its victims off almost haphazardly, taking a half-dozen or more from a school, twice that from the workhouse, an entire family elsewhere. Cinemas and pubs closed their doors, and few shops other than the druggists’ had a line-up. City streets were sprayed with disinfectant, and people tied handkerchiefs over mouths and noses to keep the flu at bay. Advertisers, seeing an opportunity to sell their products to a public hoping to avoid contracting the illness, climbed aboard the influenza cart. Everything from mints to beef teas was touted by their makers as having curative or preventative properties. Consuming Oxo Beef Cubes would “fortif[y] the system against influenza infection,” while gargling a single tablespoon of Condy’s Remedial Fluid mixed with water was billed as both a “prevention and cure.” The Dunlop Rubber Tyre Company placed ads that showed a man on a bicycle, and stretched rather far to make a link: “If the influenza fiend has had its grip on you, let your bicycle help you to throw it off. Get out into the fresh air whenever you can and ride gently along…. Dunlop tyres … mean no troublesome tyre worries to interfere with your bicycle cure.”

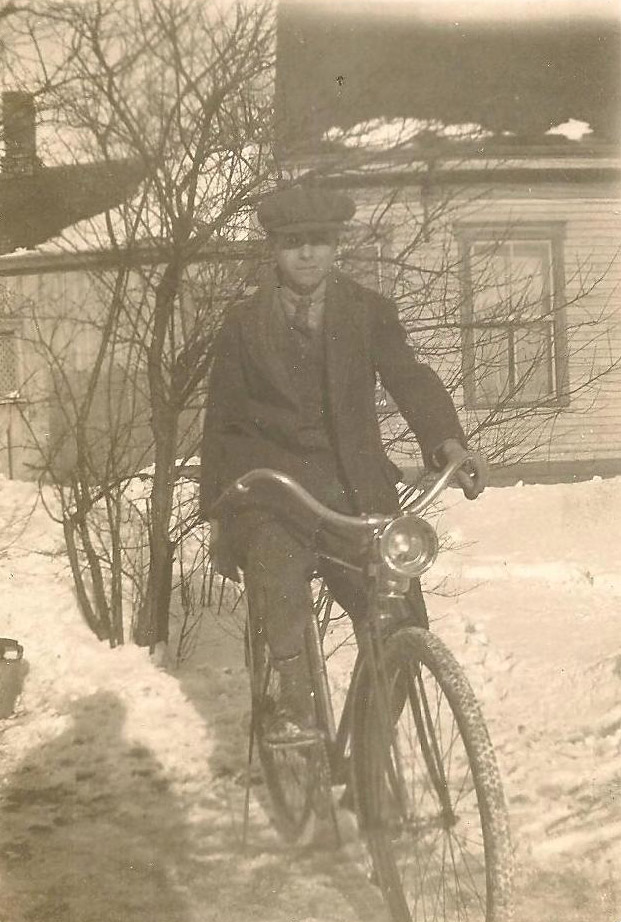

The flu carried its victims off almost haphazardly, taking a half-dozen or more from a school, twice that from the workhouse, an entire family elsewhere. Cinemas and pubs closed their doors, and few shops other than the druggists’ had a line-up. City streets were sprayed with disinfectant, and people tied handkerchiefs over mouths and noses to keep the flu at bay. Advertisers, seeing an opportunity to sell their products to a public hoping to avoid contracting the illness, climbed aboard the influenza cart. Everything from mints to beef teas was touted by their makers as having curative or preventative properties. Consuming Oxo Beef Cubes would “fortif[y] the system against influenza infection,” while gargling a single tablespoon of Condy’s Remedial Fluid mixed with water was billed as both a “prevention and cure.” The Dunlop Rubber Tyre Company placed ads that showed a man on a bicycle, and stretched rather far to make a link: “If the influenza fiend has had its grip on you, let your bicycle help you to throw it off. Get out into the fresh air whenever you can and ride gently along…. Dunlop tyres … mean no troublesome tyre worries to interfere with your bicycle cure.” Despite the dubious link, Ernie would have enjoyed the Dunlop tyre claim, and in Laindon he probably took every chance to follow the company’s advice to ride. Ernie had been an avid roller-skater back in his old Marshalsea Road neighbourhood, so the move to a bicycle was a natural progression, and all his life he would love to cycle. A photo taken several years later attests to his comfort on two wheels. He slumps casually on the seat of a sturdy bicycle, one hand dangling at his side, the other resting on the handlebar. His right foot sits on the raised pedal, his pant leg is tucked into a sock so as not to get caught in the chain; the other foot is planted on the ground, holding his balance. Dressed in a wool jacket, vest and tie and with a flat cap shading his eyes from the slanting sun, he gazes steadily at the camera. In most other early photos of Ernie, there is a Chaplin-esque look about him – a thin-shouldered vulnerability that lifts off the paper – but in this single shot, that quality is absent, replaced by a confident, relaxed demeanor.

Despite the dubious link, Ernie would have enjoyed the Dunlop tyre claim, and in Laindon he probably took every chance to follow the company’s advice to ride. Ernie had been an avid roller-skater back in his old Marshalsea Road neighbourhood, so the move to a bicycle was a natural progression, and all his life he would love to cycle. A photo taken several years later attests to his comfort on two wheels. He slumps casually on the seat of a sturdy bicycle, one hand dangling at his side, the other resting on the handlebar. His right foot sits on the raised pedal, his pant leg is tucked into a sock so as not to get caught in the chain; the other foot is planted on the ground, holding his balance. Dressed in a wool jacket, vest and tie and with a flat cap shading his eyes from the slanting sun, he gazes steadily at the camera. In most other early photos of Ernie, there is a Chaplin-esque look about him – a thin-shouldered vulnerability that lifts off the paper – but in this single shot, that quality is absent, replaced by a confident, relaxed demeanor.