Though our book is subtitled “a genealogical journey,” it isn’t filling in the family tree that excites me most. It’s the history — and the mystery! — that inspire me above all, and I suspect many genealogy enthusiasts are the same. Searching out the family story opens windows into the past, through which all sorts of other stories appear. I can easily disappear down rabbit holes researching people totally unrelated to me, but using all the same tools I’d use to find my ancestors.

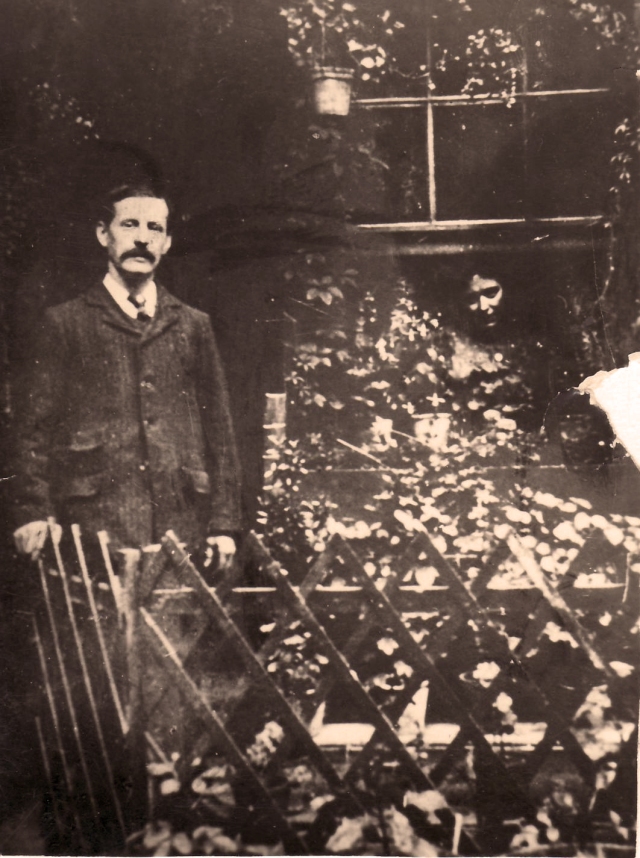

Take, for instance, two “terrors of the Borough” I came across while hunting through the British Newspaper Archive for mentions of Red Cross Street, now Redcross Way, and the Southwark family home for decades. In 1891, our great grandmother, 18-year-old Mary Anne Evans, was living there with her aunt, since her father had died and her mother had disappeared into the local workhouse. Handsome young Harry Deverill, 21 that census year, had moved into the street, too, and was working as a grocer. Soon their romance blossomed, and they were married at St Saviour’s Church (now Southwark Cathedral) in 1895. Given the timing, and the fact that Mary Anne had grown up in the street, it seems certain that they would have known of the terrors, Annie Bennett and John “Caster” Cannon. Caster — sometimes Coster and Costy — lived in the Mowbray Buildings, rough tenement housing where Mary Anne’s troubled sister Ellen also lived after her marriage fell apart and she began her downward spiral.

Throughout the 1890s, articles about Caster Cannon pop up in the newspaper archive. He was a “sweep and pugilist” about the same age as Harry, and had a dangerous reputation in the neighbourhood, less for pummelling other boxers than for pummelling his neighbours. In 1891 he and a fellow fighter were caught up in the death of a betting agent; and in 1895, he and another man living in the Mowbray Buildings were charged with striking a man in the head with sticks. The man headed up a rival gang, and his thugs and Caster’s thugs — thieves and bullies of the Borough — were engaged in an ongoing feud. Caster was “quite at home in the dock,” the press reported, “[and] conducted his case with great ability.”

The following August, the Illustrated Police News ran a piece titled “Oh, What a Surprise!” and revealed that Caster had been charged with disorderly conduct and assaulting women. He’d appeared frequently before the court for violent assaults, the paper claimed, and was “notorious as one of the most dangerous characters in the Borough.” A crowd of locals gathered outside the courthouse, anxious to hear the outcome of the charges, but they were not allowed in.

After hearing the constable and the women testify, Caster claimed, “It’s all a pack of lies. These women want to put me away from my wife. I can’t be such a bad man, for I’ve got five little children and another one expected. I wish your worship would hear what my wife has to say.” But when his wife Mary Ann was called in, the magistrate asked her if she had recently come to him for a warrant against her husband, and she answered “Yes, sir. A week ago.” The charge of assaulting his wife was added to the other charges, and “the prisoner, who seemed dumbfounded by this turn of affairs, was then removed.”

A week later, another Borough brawl erupted in Caster’s absence, and this time Annie Bennett was charged with disorderly conduct and using obscene language. Annie was a 27-year-old laundress who lived in Redcross Court, one of the dank little alleys that snaked off Red Cross Street. A constable had spotted her fighting with another woman, and though he separated them, Annie “would not go away when requested, and used disgusting language.” She said she’d “have the liver out of the other woman because she had helped to get Caster Cannon two months.” She was sentenced to 14 days’ hard labour, but it was not the first or last time she’d appear before the magistrate.

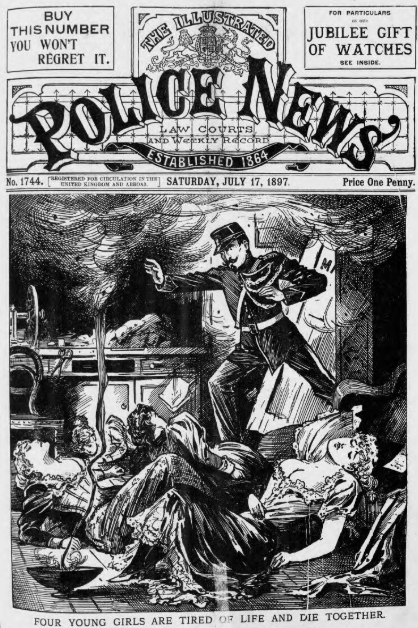

Reading on in the archive, it’s hard to muster sympathy for Caster Cannon. In early July of 1897, he approached the same magistrate, “a nervous individual seeking the protection of the court.” He claimed a gang of men had come into his lodgings in the middle of the night and threatened his life. The magistrate seemed amused by the “evident anxiety of the burly applicant,” but a week later, according to the Illustrated Police News in a piece headed “The Terror of the Borough,” Caster had indeed been beaten, and sat in court with his head “a mass of bandages.”

There were in all some six or seven charges and counter charges, to which the magistrate gave a very patient hearing, occupying nearly two hours. … Mary Shaw, wife of a costermonger, was the first complainant against Cannon. She alleged that Mike Smith, an ex-convict in her husband’s employment, refused to yield up to Cannon a shilling out of the day’s takings belonging to her husband, whereupon Cannon knocked him senseless with a blow in the stomach. The witness remonstrated, and Cannon struck her in the face, and threw a can of beer over her. Subsequently he emptied a quantity of filth over her barrow-load of strawberries. … Cannon was accustomed to demand money and beer of all comers. People in Redcross Court had put up with it, under fear of him, for years past. But when he moved to Queen’s Court, a few weeks ago, he tried the ‘same game’ with less success. She was aware that a party was made up to break into Cannon’s house, which was next door to hers, and to drag him out for punishment, but she was not the organiser of the party, nor did they rendezvous at her house. It was not true that her grievance against Cannon was that he objected to her boiling whelks in the copper, which belonged jointly to the two houses. Mike Smith corroborated Mrs. Shaw’s story, and charged Cannon with assaulting him, simply because he would not pay toll to the ‘bully of the court.’ … [He] was not one of the party who stormed Cannon’s abode at three o’clock in the morning, dragged him out of bed, and beat him black and blue, but he was glad to hear what had happened. … Passing from the dock to the witness-box Cannon gave his version of what had happened to him, and bitterly complained that a ‘mob’ of fifteen or twenty men broke down his door, smashed his furniture, beat him with sticks and pieces of iron while he was in his shirt, and would have killed him ‘like a rat’ but for the arrival of the police. … After further evidence, the magistrate said it was high time these disgraceful fights were put an end to, and sentenced Cannon and Selby, both of whom had been frequently convicted, to four months’ hard labour, and Smith to one month. On leaving the court, Selby rushed savagely at Cannon, and was narrowly prevented from again assaulting him.

From then on, mentions of Caster as “the terror of the borough” begin to dwindle. But his defender, the laundress Annie Bennett, earned the same nickname for her ongoing wild behaviour. She was a small woman with sharp features and a quick tongue, her arms “freely tattooed” with the names of various lovers — a jealous woman once tried to scrape off one of those names with broken glass, but Annie fought back with fervour. In 1899, when she was charged with being drunk and disorderly, she was sentenced to a year in an inebriates’ home in Bristol. She called the constables liars who wouldn’t let anyone off, and let loose a stream of “violent language” as she was taken from court. One article said she was a habitual drunkard who had had many similar convictions, and had “frequently distinguished herself in the many skirmishes and battles with which the history of Redcross Court is studded.”

But I always wonder about the stories behind these stories, and the clues that suggest different tellings, different views of these old slums of Victorian London and the people who lived there. It was home to them, after all, and the people who often wrote about the slums were outsiders, with an outsider’s vantage point (just like me, now). Redcross Court, where Annie Bennett lived, “possessed the most undesirable reputation as any slum in London,” but after eight months of her sentence, Annie escaped the inebriates’ home and made her way straight back there. She was caught, and sentenced to three months in prison, and when that was over, she returned to the Borough immediately, only to be caught up in a brawl that landed her in front of the magistrate. He asked her why she’d escaped in the first place, only to cause herself more trouble, and she answered that she’d heard Redcross Court — dilapidated and overcrowded — was going to be torn down by London County Council, and she thought she would like to see it again before it was no more. The article mocks “the sentimental side” of “the lady in question,” and her wish to see “the last of her much-beloved slum.” But at the same time, her wish rings true, and makes me all the more curious about who she really was, and what her neighbourhood was like from an insider’s perspective.

♦

Sources

“Borough Roughs.” South London Chronicle, 10 August, 1895

“Caster Cannon Again.” South London Chronicle, 5 October, 1895

“Oh, What a Surprise!” Illustrated Police News, 22 August, 1896

“Life in the Borough.” South London Chronicle, 29 August, 1896

“The Rival Champions.” Daily Telegraph & Courier (London), 4 November, 1896

“‘Caster’ Cannon Again.” South London Chronicle, 3 July, 1897

“The Terror of the Borough.” Illustrated Police News, 17 July, 1897

“‘Terror’ Goes to Bath.” South London Press, 3 June, 1899

Page 5. South London Chronicle, 14 July, 1900.

“Habitual Drunkard’s Escape.” South London Press, 17 January, 1903

Great story of Caster the bully. Every neighbourhood seems to have one. And I can understand Annie wanting to go back to the street that was her home, however horrible in our eyes.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Common experiences, values and familiarity to name just a few make people feel a part of a community. This is not always recognized or appreciated by an outsider who doesn’t share the same societal values, and sometimes also not appreciated until one leaves that community and still longs for it and the memories made there. Great post!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Just started putting together my family tree and discovered this site! My great great grandfather William TOAL lived with his family at 1 Red Cross Court in 1871 so your story was particularly interesting. Still lots to do and learn but really enjoying the research despite making rookie errors and presuming associations and later paying for my mistakes! I’m stuck with any further info on William Toal so anything you might have come across during your research would be really useful. Dean

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Dean. Thanks for getting in touch. You are going to have a fascinating time researching this area! Much of our book is set right in these streets throughout the 1800s, and there was no end to the interesting material we came across. It is as much a story of the time and place as it is the story of our family. If you want to get a better idea of the world your ancestor inhabited, I would highly recommend you read the book (of course!) but also check out places like the British Newspaper Archive, where you can search street names and people’s names, and also the Charles Booth website, https://booth.lse.ac.uk/map/14/-0.1174/51.5064/100/0. Enjoy the journey!

LikeLike

Hi, I have a photo of a group of men about to go off on a day out stood in Red Cross Court from about 1900, but I don’t know how to post it!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Interesting! I’ll send you a message…

LikeLike

Pingback: Red Cross Neighbours – The Cowkeeper's Wish