Tiny glowing reviews from readers are trickling in for The Cowkeeper’s Wish in various places. I especially love one that describes the setting as “the stinky London of Charles Dickens” and calls the book “a vivid story about regular people in the real world.” That’s what Dickens wrote about too; his characters were fictional, but the world he placed them in existed in all its sooty splendour.

Tiny glowing reviews from readers are trickling in for The Cowkeeper’s Wish in various places. I especially love one that describes the setting as “the stinky London of Charles Dickens” and calls the book “a vivid story about regular people in the real world.” That’s what Dickens wrote about too; his characters were fictional, but the world he placed them in existed in all its sooty splendour.

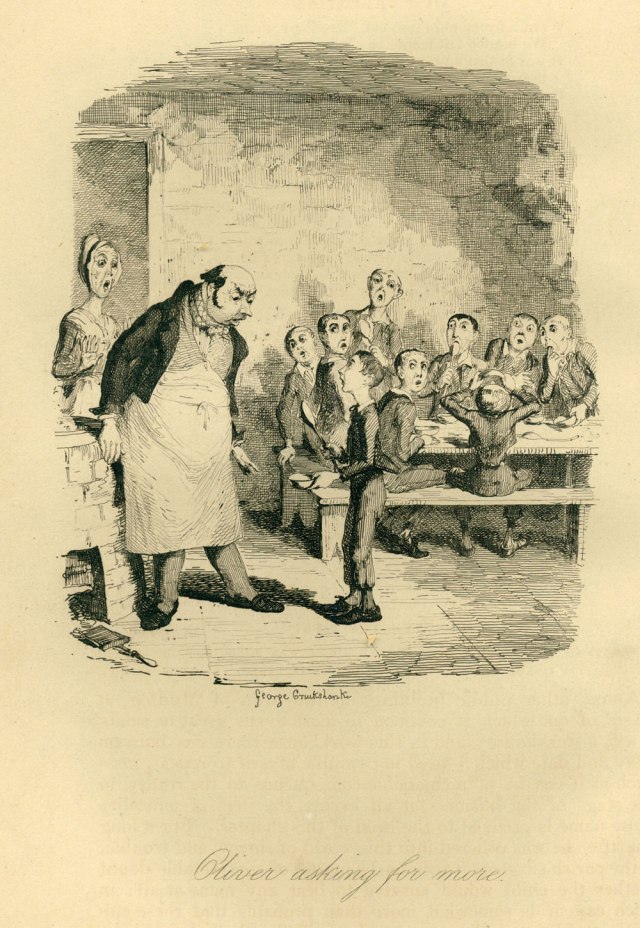

Our ancestors, Benjamin and Margaret Jones, arrived in Red Cross Street in Southwark in the late 1830s, around the time Oliver Twist began appearing in monthly instalments in Bentley’s Miscellany. Some say the workhouse in Oliver Twist was modeled on the Mint Street workhouse, steps away from our ancestral home, and condemned by the Lancet as “a den of horrors.” Though the esteemed medical journal called for its removal and labeled the tramp ward “an open sty,” the workhouse remained in place until the 1920s, and is a landmark in our own family history. The Mint Street workhouse makes regular appearances in our story, and was sadly the eventual home for Benjamin and Margaret’s daughter, “Lazy Mary.” Family lore says that Mary entered the workhouse after her husband died, because she was too lazy to care for herself. There is more to the story, of course — no one enters a den of horrors out of laziness. But the fact that the story exists speaks volumes about the stigma attached to workhouse “inmates.”

Dickens had strong ties to our family’s neighbourhood. When he was just a boy, his father was sent to Marshalsea Prison under the debtors’ act. Some of Dickens’ siblings and their mother lived there too while the sentence was carried out, but Charles, just 12 at that point, lived nearby on Lant Street and worked in a blacking factory. Lant Street appears in the bottom left area of the map shown, and the letters “BD SCH” stand for “board school.” Many members of our family attended the Lant Street Board School, which opened in the late 1870s, and served the poor children of the area. In the late 1890s, the annual school report noted that “in a low locality like this,” a more distinctive school name connected to the history of the area might be a good idea. And since Dickens had already been commemorated in many placenames throughout the Borough, “Would not therefore Charles Dickens School, Lant Street, Southwark, be an appropriate name for this school?” It took years more for the change to come about, but finally, by 1912, the name was in place. Our grandmother Doris and her siblings attended, and so did many of their cousins.

Dickens placenames pop up throughout this neighbourhood: there’s Quilp Street, Copperfield Street, and Dickens Square. And tucked in behind Red Cross Street (now Redcross Way) is Little Dorrit Playground, put in place by the London County Council in 1901 to address the notion that childhood was “blighted” in this impoverished area. One writer claimed the children here were “more woe-begone, unwashed and unhealthy-looking” than any in the city. If you ask me, the girls above look ordinary and even lovely enough — but earlier pictures do show children in bare feet, with ragged clothing and an unkempt appearance.

If the playground was meant to brighten children’s lives, a social reformer wandering through shortly after it was put in place was not impressed. The space was surrounded by high walls. It had one gas lamp in the centre and a drinking fountain. “It is essentially a playground for rough children, no seats because of the encouragement to loafers, nor any caretaker. I have only been there during school hours,” he admitted, “when few children were about.”

The area has changed, of course, since those “stinky” days. While much of our years-long research was done online, we visited London to see the site of our story for ourselves. It gave us chills to walk along Redcross Way, up past Crossbones Cemetery, and over to Borough Market. We ate lunch on the grounds of Southwark Cathedral, where Benjamin and Margaret and others in our line were married, and we studied in the local history library, right next to St. George the Martyr Church, where Little Dorrit was married, and where a wall from Marshalsea Prison still stands. These are just some of the remnants that are left from the years when our family lived and loved here.

♦

For some wonderful pictures and stories about Dickens’ connections to Southwark, visit the Southwark Heritage Blog.

Oh, what wonderful memories of our trip to Old London. Much better now than the times written about in the story. That “stinky” world is so well portrayed in The Cowkeeper’s Wish.

LikeLiked by 1 person

You would have enjoyed the guided walks around Dickens’ London an elderly friend, sadly missed, used to lead. She would dress in period costume and take on some of the characters from Dickens’ novels using various voices. She and her husband were heavily involved in the Dickens’ Festival in Rochester too.

LikeLiked by 2 people

That does sound fun!

LikeLike

Agreed. Anyone who loves Dickens will love this book which brings these times to life in vivid detail. The archival details are remarkable!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks Sara! I want to put that on the book jacket! 🙂

LikeLike

Wonderful images – both text and pictorial!

LikeLiked by 1 person