Tracy and I are heading off to London, Ontario, this weekend to talk about The Cowkeeper’s Wish, so we are naturally thinking about our grandmother, Doris Deverill, whose story first inspired us to write the book. We used a wealth of resources to piece together the century-long tale, but the most treasured ones came from our own family archive.

The following article tells a little about that collection, and some of our mishaps along the way. The story first appeared earlier this year in the Alberta Genealogical Society’s journal, Relatively Speaking.

•

Several years ago my sister and I set out to tell the story of the British side of our family, from our Welsh 3xgreat grandfather, who walked to London, England, with his wife and his cows in the 1840s, right on down to our grandmother’s marriage nearly a century later in London, Ontario. We aren’t professional genealogists by any stretch, but rather writers who share a passion for family history and great stories. Armed with an abundance of curiosity, we scrutinized all the essential documents: census, birth, marriage and death records, and also workhouse and asylum ledgers, old newspapers, passenger lists and immigration papers. We looked everywhere for our people, and got chills whenever we found them. Some of the loveliest material had been passed down from the very people we were writing about: letters and postcards with strings of x’s, embossed funeral cards, a lucky penny that went through the war with a sailor-great-uncle, and an array of photographs. Treasured possessions, all, and a gold mine for researchers who like to read between the layers of everything they encounter.

Our grandmother, Doris Deverill, was born in Whitechapel in 1910, and emigrated to Canada in 1919. Her childhood had been infused by war, and both her parents were dead. She was now under the care of a family friend named Martha, a woman she loved dearly, but it must have been devastating to leave her siblings, her friends, and everything she’d known to cross the ocean and start somewhere new. Maybe it was this monumental loss that caused her to paste the postcards she received, for years afterwards, into a scrapbook. Or maybe it was just a young girl’s admiration for pretty pictures. The cards featured sweet little girls holding kittens or puppies, the images often tinted to give them an even more tender look than they’d have in sepia. And the text usually matched the pictures’ sentimental themes:

But when I say the postcards were pasted into the scrapbook, they really were pasted. It’s impossible to know, now, what she used to adhere them to the pages; though many of the cards date from the 1910s and 20s, she may have re-glued them later, or even started the project later in her life, gathering the loose pieces she’d collected over the years. Regardless, it was obviously the cards themselves our grandmother had been preserving rather than the messages on the backs. She would never have imagined that, long after her death, anyone would want to know what the postcards said or who they were from.

We, of course, were itching to know. As we flipped carefully through the book, turning the thick pages, we pried at the corners of the cards just gently to test how easily they might be released, curious to know what secrets would spill forth once we saw them. For though so much can be gleaned from historical records, these personal artefacts had been held by the very people we were searching for. A postcard had been chosen just for Doris in some little English shop by an auntie, a sister, a cousin; had been written on and stamped and mailed, had traveled all that distance by ship, just like Doris herself, and then been brought to the door by the postman, and she had happily received it and devoured the message with her fingers carefully placed at the card’s edges, no doubt, so as not to muss the pretty picture.

Over the years of our research, we often longed for more of these kinds of resources to help us unravel the family story. We’d sometimes joke with each other by email as we slogged through the many dry spells of our research periods: “You’ll never guess! I found the cowkeeper’s wife’s diary from 1842! She recounts their travels from Wales; how long it took them and all the strange things they encountered, and their first impressions of London when they landed there, the cows weak and weary and their own feet blistered and sore! There are delicate pressed wildflowers inside, and little drawings in the margins!”

Of course, there was no such diary; and on actual records, the cowkeeper’s wife had signed her name with an x, so likely she could not have written one anyway, even if she’d cared to. But we did have Doris’s scrapbook – and with a variety of approaches we had some success in releasing the postcards from an almost century-old grip. Some were sawed free with dental floss; some were steamed or blow dried; some soaked in tiny baths. It was a bit like taking the scrapbook to the spa, and pampering it to give over its secrets. And it was beyond exciting, even though, to be honest, most of the postcards had fairly mundane messages, such as:

Another featured a hand-drawn rose on its front, meticulously painted, and signed Ernest Biss. We didn’t want to soak this one for fear that the rose would disappear, so we carefully steamed it loose and watched it curl at the edges. The rose suffered a little from our efforts, and we lost some of the message on the back – but once again, it seemed disappointingly spare anyway. But we had a name, at least, and with a bit of sleuthing we discovered that Ernest was about 19 the year Doris left for Canada; he was her neighbour in College Buildings in Whitechapel, and his father was the verger at nearby St. Jude’s church, where she was baptized. Their families would have shared the same dismay when the Titanic went down, taking with it the church’s beloved minister Ernest Courtenay Carter and his wife Lilian. Doris was given the middle name Lilian for Lilian Carter; was Ernest likewise named for Ernest?

Another featured a hand-drawn rose on its front, meticulously painted, and signed Ernest Biss. We didn’t want to soak this one for fear that the rose would disappear, so we carefully steamed it loose and watched it curl at the edges. The rose suffered a little from our efforts, and we lost some of the message on the back – but once again, it seemed disappointingly spare anyway. But we had a name, at least, and with a bit of sleuthing we discovered that Ernest was about 19 the year Doris left for Canada; he was her neighbour in College Buildings in Whitechapel, and his father was the verger at nearby St. Jude’s church, where she was baptized. Their families would have shared the same dismay when the Titanic went down, taking with it the church’s beloved minister Ernest Courtenay Carter and his wife Lilian. Doris was given the middle name Lilian for Lilian Carter; was Ernest likewise named for Ernest?

What became of Ernest Biss and his drawing abilities? We can follow him in various documents through the years, but his link with Doris remains a mystery. Did they correspond after Doris and Martha left for Canada? If so, there is no trace of an exchange, and only the rose remains.

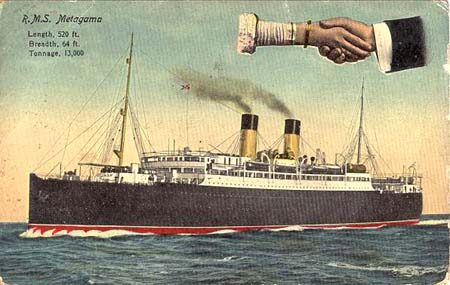

The wordiest postcard in Doris’s scrapbook depicted the ship Metagama, which brought Doris to Canada. Metagama was a passenger ship launched in spring 1914, but soon pressed into service as a troop carrier during WW1. In 1919, when Doris was on board, there were still plenty of soldier-passengers making their way home. Doris and Martha were just two of 1,300 souls on board, arriving in Montreal after a nine-day journey. From there, before boarding a train to London, Martha sent the card to Doris’s brother Joe. Doris wouldn’t see Joe again for about 40 years, which means he either sent the postcard back to her as a keepsake, or held onto it all that time and offered it in person, when she returned to her birthplace as middle-aged woman.

We tried all the methods to free the postcard from the album, but when it came loose the writing was still covered by a fuzzed layer of the album’s paper. So we kept steaming, peeling, stopping, discussing. Then we’d peel, stop, discuss some more. The postcard was like a scab that shouldn’t be picked – but imagine what it might tell us, having been written on the very journey that opened the door for our own existence. Surely it was a little diary of sorts, but real this time, and in our possession!

In the end, we got the layer of album paper off of the post card, but most of the words came away with it. We held the bits of paper up to the light, and we peered at all the remnants with a magnifying glass, but much of the message had been lost to us. We were left with:

Arrived quite safe this morning at 6 o’clock. We had a very … Write you later on.

Had a very what? Difficult journey? Wonderful journey? Big breakfast? Bad fight? Tearful goodbye with fellow passengers? Though the family correspondence had never been terribly revelatory, the loss still felt awful, since first-person accounts in the histories of ordinary people are rare wonders, no matter how mundane. And yet, our story got told anyway; built bit by bit like an intricate collage. When I think back to our wrong turns, and to the brick walls we encountered while searching for clues, I realize that it isn’t important for me to have all the answers, and that part of the beauty of this kind of research is in the very mysteries that can never be solved. For after all, each time a new person is added to a tree, more blank spaces inevitably open. Every “answer” prompts new questions, and keeps the journey, rather than the destination, in focus.

I so enjoyed this post Kristen, especially thinking about life from Grandma’s nine year old perspective. What a brave girl she was, and how blessed she was to have Bebbie raise her.

Also, I am reminded that Grandma collected items for scrapbooks for each of us, her twelve grandchildren, so she did cherish scrapbooking before it was the craze it is today.

LikeLiked by 2 people

So true Michele!

And yes re Bebbie. She really gave herself over to Grandma.

LikeLike

Fascinating account which I fully sympathise with 😀

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh, those scrapbooks. I think it was a craze in those days, and even later when I was a child we used to cut out pictures from newspapers and magazines of spectacular events or of the Royal family and glue them on the pages. It was fun, later, maybe on a rainy day, to sit and look through the pages. But those postcards from Doris’ childhood with the little messages for a Happy Birthday or announcing a coming visit are really priceless.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I have two beautiful scrapbooks like the ones you describe, probably from the 1940s. I got them at a flea market, and every inch is covered with clippings or pretty pictures from newspapers. They’re really fun to look through all these years later, even though I have no connection to the people who made them!

LikeLiked by 1 person

This is wonderful! I so wish we had some documentation from my grandmother’s life which Kristen kindly shared on her blog. Just a few photos, but at least that’s something. This is a real treasure and thank you for sharing.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: Part 3: A WW1 Barnardo’s Boy – The Cowkeeper's Wish