I was in London, Ontario, recently, giving a workshop about the many wonderful resources we used to research The Cowkeeper’s Wish, and afterwards I was approached by Gord Wainman, one of the participants, who told me a bit about his father, “a very troubled soul” who’d served in the First World War.

I was moved by the story and asked Gord to share it here, and am posting it the day after Remembrance Day to underscore the idea that war wounds, both mental and physical, continue long after war has ended. Here, in Gord’s words, is the story of Stanley Holmes Wainman and his family.

♦

A year before he died, my father made a final request. He wanted to be buried in a simple pine coffin with his body wrapped in an old wool army blanket. He made me promise I would respect this wish. His reason for this spartan request — to honour the many friends and comrades who had died on the World War 1 battlefield.

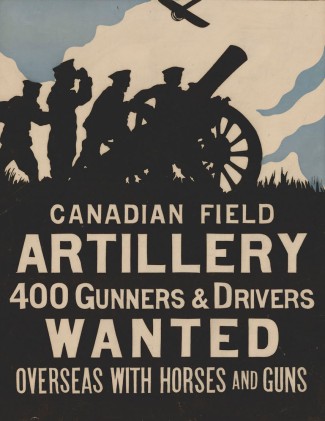

He fought at Vimy Ridge and was part of the final advance to Passchendaele only to become a casualty two weeks before the war ended. He was a bombardier, overseeing the firing of artillery and accompanying the horses and Limber wagons into battle. At least twice, he was sent to “gas” school where soldiers were trained on how to respond to mustard gas attacks. Not the best military “occupation” for such a gentle man who worked as an accountant before joining the army.

My father was 21 when he joined the 40th Battery, CFA in Hamilton on Sept. 17, 1915. Six months later he was in England but was hospitalized shortly after he arrived because he had German measles. He landed in France on July 14, 1916, and except for an 18-day leave and a brief hospital stay for impetigo, he was in the field for over two years.

He never spoke of his war experiences. Until I found his records, I did not know he was a bombardier. I did not know about the “gas” schools. I did not know that his right foot was partially crushed by a Limber wagon near Valenciennes 20 days before the war ended. He was evacuated but his return to Canada was delayed by several months until he could walk again.

If the luggage he brought home was sparse, his emotional baggage was huge and its weight affected us all – my mother, my brother and myself. We lived with his depression. We all bore his pain.

Several family friends described my father as someone who always seemed to have a “permanent cloud” over his head. In the 32 years I knew him, I never remember hearing him laugh. Even his smiles were forced.

After the war, he spent most of his life devising a financial solution to the world’s ills which he believed would end all wars. He wrote a book, convinced it would change the world. He expected my brother and I to continue his mission.

While he never talked about his war experiences, he did say that he and his fallen friends had been “duped”. A genius with figures and a self-taught thinker, he was going to correct that. He was obsessed, spending little time with wife or sons.

He and my mother were what I’d call “progressives” today, meeting during the founding convention of the United Church of Canada. He was a Methodist, my mother an Anglican. They paid a price as they were initially shunned by both families.

In 1929, ten years after he returned to Canada, my father lost his job when the Depression hit. He rode the rails to harvest in the West and tried to make money painting barns in Northern Ontario. My mom and brother suffered. Several years ago, I read a heartbreaking letter my father wrote to my mother while he was up north begging her to help their son David understand why they lived in such desperate conditions, above a store on St. Clair West in Toronto.

By the mid 1930s, my father ended up in Windsor, Ontario, where he stayed. That’s when his obsession about ending war and human misery became all-consuming. He developed a financial system he called “The Golden Rule Exchange.”

Living with constant supper-time lectures on the evils of greed and the golden rule solution, my brother Dave fled home at the age of 17. I was two and idolized my big brother.

A few years before Dave died in 1997 at age 69, he told my wife, in tears, that he was racked with guilt for leaving “that poor little fucker” — me — to fend for myself in that toxic environment. “There was no laughter or joy in that house”, he said.

Considering all the conversations involving PTSD, we now know that’s what my father suffered from. Back then, if there were physical signs, it was called “shell shock”. But he showed no outward signs.

The Anxiety and Depression Association of America outlines seven symptoms. If a person has two or more, they likely suffer PTSD. My father scored on six of the seven: exaggerated expectations of self, other or the world; persistent anger; diminished interest in participation; detachment from others; inability to experience positive emotions; nightmares.

When I was eight or so, Canada entered the Korean War. To make his point about the horrors of war, my father took me to see the silent 1930 movie All Quiet on the Western Front, based on a book by Erich Maria Remarque, a German veteran of World War I. Looking back, I know my father wanted the movie to speak for him.

The impact on me has been periods of depression. My wife sometimes says… “It’s time to leave now Stanley”, not out of disrespect for my father, but to shake me out of my mood.

Stanley Holmes Wainman died in 1974 in the old “Parkwood” military wing of Victoria Hospital in London, Ontario. My brother and I knew it was the end of a long painful life. My mother Leota May died 14 years earlier when I was 17. I was a late comer. My father was nearly 50 when I was born in 1942. I was named after Major Gordon H. Southam, a unit commander with the 40th who was killed in action in 1916.

Laid to rest in a pine coffin and wrapped in the wool army blanket he requested, Stanley Holmes Wainman was buried beside his wife Leota May. A small family group attended, my brother Dave and his family and me with my wife and daughter.

Before he died, I told my father I found a blanket and that seemed to comfort him. Then he said something that stunned me considering he lived his life convinced he could solve the world’s problems.

“I always thought I knew the answers, but now I’m not so sure.”

I didn’t cry at his funeral. Four years later, out of the blue, I began to sob uncontrollably, with no idea what triggered it.

Despite our bad times, he was always there for me when I got in trouble. Despite it all, I still miss him.

Gord Wainman

Reblogged this on War Diary of the 18th Battalion CEF.

LikeLiked by 2 people

My grandfather was in the Royal Horse Artillery & sent to France at outbreak of WW1 …. he had similar experiences, & also never spoke about the war to his wife & daughters ( my grandmother, Aunt & mother.) However he did talk to my Uncle ( his son) towards the end of his life ( He died in 1966) I remember him as a very grumpy ( To my childish eyes) & taciturn man. Now I realise why! He returned to the “Land fit for heroes” to find he, like many others, were not welcomed by employers. He lived through the1926 General Strike & the Great Depression. I now salute him & all his generation

LikeLiked by 3 people

Thanks for this Julia. The “never speaking” is something we heard a lot about following our WW2 book, The Occupied Garden, as well. Such a difficult thing for so many — not just the people who served as soldiers but their families too; even the members who came along long after the war was finished were impacted.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you Gord Wainman for the story about your Father. His struggles will be familiar to many. The tentacles of emotional pain reach far and wide into families who have dealt with PTSD, anxiety and depression. These are difficult but important stories to hear.

LikeLiked by 1 person

We have similar experiences in the family because of Afghanistan. War is just a horror that mankind cannot seem to stop. Thank you Gord and Kristen for this heart-wrenching story.

LikeLiked by 2 people

My father served in the 18th Battalion and was wounded in the Battle of Courcellette losing a kidney as a result of his wounds and eventually died in Westminster Veterans Hospital in London Ontario in 1956. As a young boy I can remember visiting him and talking with dozens of veterans from WW! and WW2 in the ward he was in. Many with no family. This branded on my brain. My mother came from East London England being born in 1900. She came from poor conditions and ended up in Palmerston Ontario with her mother and step-father as her father had died in 1902. She fled to Guelph at the age of 14 as a result of sexual abuse by her step-father and became a domestic servant. She met my father in 1920 and had a family of seven, one dying at 18 months and the other five growing up during the depression, all leaving home when they reached the age of 16 as they lived in poverty as we would now call it.

I was born during WW2 and only knew my father for 12 years. He was a very gentle man and his war experiences were seldom talked about. One thing I have always remembered he told me.

” You couldn’t feed your family on medals”. I didn’t know what he met until he was gone. My mother had become an alcoholic during her life and when my father died she lived on a widow’s war veterans pension and I also remember having very little, growing up doing so much on my own and very lonely. I was able to serve in the navy and also become an engineer and now have a marriage of 52 years with two devoted sons and five top of the line grandchildren. What I also have is clinical depression (Bipolar) and anxiety disorder for the past 25 years and traceable back to my beginnings. I’m telling you my story as you can see how war and roots of abuse and poverty may carry on into other generations. Thank you.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Murray, thank you so much for sharing this. It is really astonishing sometimes when we learn how difficult things were for earlier generations — but I think you are so right, that the troubles filter down. Just one of the reasons for the fact that understanding our family history can often help us understand ourselves. Your long marriage, and the presence of your children and grandchildren must be a great comfort to you.

LikeLike

Thank you, Murray for this very poignant story. Again it just shows the terrible lasting effects of war. I am so glad that, despite some health problems, you have had a full and happy life.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thannks for posting this

LikeLiked by 1 person